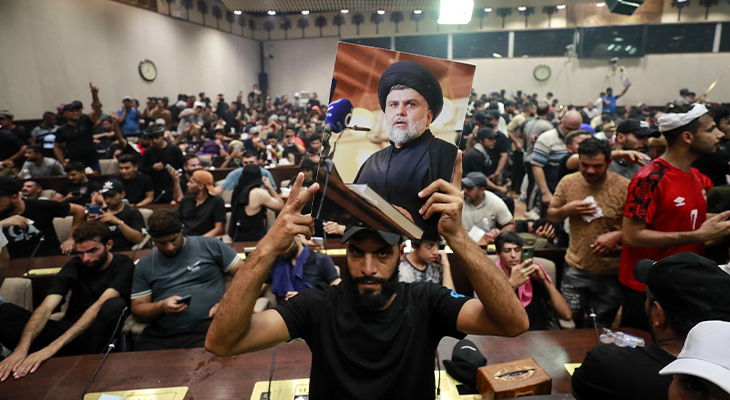

Protestors had been camping inside Iraqi’s parliament for over four days when Iraqi Shi’ite leader Muqtada al-Sadr instructed his supporters to leave the building, but to continue their protests outside the building’s offices. In a tweet, Mohamed Saleh al-Iraqi, a senior pro-Sadr loyalist, told hundreds of supporters to leave the parliament building in the capital, Baghdad, within 72 hours and join fellow Sadrists at an “encampment in front of and around the building”.

Amid the ongoing tensions, Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa Al-Kadhimi encouraged a “national dialogue…through the forming of a committee to work on a roadmap”, adding that “all Iraqi factions were asked to maintain self-reservation and seek de-escalation”. Al-Kadhimi’s invitation has been endorsed by the Sunni speaker of parliament Mohamed al-Halbousi, a senior Coordination Framework Official (the Coordination), and Ammar al-Hakim, leader of the Hikma Movement (National Wisdom Movement-NWM).

Escalations continue

Signalling a deep rift across the Iraqi political spectrum, there has been three noteworthy developments in Iraq of late, which may be summarised as follows:

1. Sadrist escalation:

Iraqi Shi’ite leader and cleric Muqtada al-Sadr is sending a message: a government which he does not endorse cannot pass. He could stall Iraq’s political process by instructing his loyalists to take to the streets in Baghdad and beyond. When the Coordination nominated Mohammed Shia’ Al Sudani, al-Sadrist members of parliament resigned in protest. Sadrists later stormed the parliament on July 27, but al-Sadr soon instructed them to withdraw. This may have been his warning signal to the Coordination, but the latter, having been unyielding on their candidate, drove the Shi’ite cleric to order his supporters to force their way into the parliament again two days later, impeding parliamentary session to elect a new president.

On August 2 Sadrists broadened their protests to other governates: Karbala, Basra, Dhi Qar, Qadsia, Muthanna, Babylon, Wasit, and beyond in northern and eastern regions. Al-Sadr also encouraged tribes to join the protests, and at least 6 major tribes did, many of whom released statements in agreement with al-Sadr movement’s proclamation for a ‘radical reformation’.

2. Counter protests:

The Coordination in turn called for rallies in the Green Zone in response to the Sadrists. Thousands of Coordination supporters joined, including major tribes, active groups (some of which are Iran-backed militias, such the Khazali Network, led by Qais Khazali), the State of Law Coalition, and the NWM. Al-Sadr’s rival Nouri al-Maliki has been endorsed by the Coordination supporters. Chants supporting al-Maliki would be heard through the streets. This indicates that the Coordination bloc supports al-Maliki, who in turn endorses al-Sudani. The movement clearly wants al-Maliki to remain part of the political scene and is strongly against persecuting him in light of recent leaks. The Coordination protests, however, were rather small in number and did not continue for long; they were disbanded eventually.

3. Preparing for armed confrontation:

Sadrist militias were quickly dispatched in key areas just outside of the capital city. Al-Sadr may be preparing for an attack instigated by Iran-backed Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) aiming to disperse the Sadrist parliament siege. Meanwhile, Iraqi security forces had not interfered in ongoing protests, which may indicate an ongoing coordination between al-Sadr and Al-Kadhimi.

Calls for de-escalation

A number of positions taken by Iraqi factions, as well as Iran, may be summarised as follows:

1. Calls for Sistani to mediate:

For the past ten months Grand Ayatollah Sayyid Ali al-Husayni al-Sistani has kept away from the ongoing rift over forming the new government. He refused to meet any Iraqi officials. Yet, the latest protests and the siege of Iraqi parliament may influence a change in the Grand Ayatollah’s position. Religious and political leaders have been seeking Sistani to prevent the situation from escalating any further and sliding into violence.

2. Efforts to reach a resolution:

Many faction leaders have called for dialogue, most notably an invitation by Hadi al-Amiri, leader of Fatah Alliance, to the Coordination and Sadrist movement to join the negotiation table. Sadrists accepted the invitation, with a key condition: Al-Amiri’s bloc must withdraw from the Coordination alliance. Sadr’s message to Iran may be that he is not opposed to all Iran-backed factions, but only to al-Maliki’s bloc. Yet al-Amiri is unlikely to stand down, given he is in thrall to Iran, which wouldn’t allow one of the strongest Shi’ite blocs in Iraq to be disassembled.

Another invitation was put forward by incumbent PM al-Kadhimi. The only way out of the current deadlock in his view is to respect Iraqi institutions, cooperate with national security agencies, and sit at the negotiation table. Supporting this view is Masoud Barzani, leader of the Kurdistan Democratic Party. Barzani proposed early elections, as did other political and religious leadership across the Iraqi political spectrum. These voices are calling for a much-needed sustainable resolution to the ongoing stalemate.

3. Ongoing confrontation between al-Sadr and Iran:

Iran’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson said the ongoing developments in Iraq are a matter of national concern and only Iraqis could bring about a resolution. Yet Iran has taken a different approach on the ground by escalating its confrontation with al-Sadr. Iran’s commander of Quds Force Esmail Qaani met with the Coordination on July 27 and instructed the nomination of Al Sudani, despite Sadr’s opposition. Qaani a second time met senior leadership of the Coordination and PMF, though this instance instructed them to avoid escalation with al-Sadr, which may explain the Coordination protestors dispersing short after.

Iran nevertheless is in opposition to al-Sadr. Headlines in state media have claimed that al-Sadr is a threat to Iraq’s political prosperity, branding Sadrist protests as “riots” and “vandalism”. One state-back newspaper published a photograph of the Coordination protestors with the caption: “standing up in the face of riots in Baghdad”. Iran’s orchestration of such media stories, portraying Sadrists as perpetrators, shows Iran is still unwilling to make any concessions to forming a new government or holding early elections, for it fears the Coordination, Iran’s strong affiliate in Iraq, could lose its ground.

Open scenarios

Considering the above, Iraq could go through one of the following scenarios:

1. Early elections:

The deadlock caused by Sadrist ongoing protests vis-à-vis the Coordination’s persistence on al-Sudani may lead in the end to the dissolution of the parliament. al-Kadhimi would remain caretaker PM until new elections are held.

2. Accepting al-Sadr’s demands:

Mindful they may well lose majority in new elections, the Coordination would accept al-Sadr’s demands eventually. But this option seems unlikely, for it would diminish al-Maliki’s influence in the new government, while strengthening al-Sadr’s grip on Iraq’s politics. Iran’s influence in Iraq would wane too as a result, which Tehran seeks to prevent.

3. Armed conflict:

If the stalemate continues, Iraqi rivals may end up in armed conflict. The Coordination might attempt to hold a parliamentary session outside the parliament’s building in the Green Zone where Sadrists have been camping for weeks. PMF militias could attempt to break the Sadrist protesters, which would lead to violent conflict. This scenario, however, is Iran’s least preferred. Not only would Iran’s influence be diminished, but it would have to face a rapidly growing popular resentment across Iraq. Yet the chances of a parliamentary session taking place are quite slim. First, there is the ongoing understanding between al-Sadr and al-Seyada coalition, which the parliament’s speaker is a senior leader. Second, parliament’s speaker had announced the suspension of parliament by invoking his constitutional power under Article 50; parliament’s work cannot resume until the speaker lifts the suspension.

It may be concluded that al-Sadr’s popularity is growing more in comparison with the Coordination. Al-Sadr’s influence may compel the Coordination to sit at the negotiation table to find an exit to the ongoing political stalemate. The alternative, to everyone’s detriment, is sliding into violence. The Coordination may have finally realised that the Sadrist Movement is too significant to be circumvented.