Details of the Iranian budget for the next year was among the major causes behind the recent nationwide protests that erupted on December 28 2017 in Mashhad City. The leaked budget included the introduced cuts in social subsidies, about a 50 percent increase in fuel prices, while military spending was significantly increased to support the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps’ (IRGC) involvement in Middle East conflicts. This reflected a growing gap between current and military expenditure allocations.

But Iran’s public budget suffers other problems, including the lack of transparency and accountability, and weak oversight on government expenditure and the wider public sector, which boosted rampant corruption practices as international corruption indices show.

There are views that the Iranian government needs to pursue a wider approach to address the consequences of recent protests that may not be limited to reconsidering priorities of public spending but also require a new unified financial system to guarantee transparency and accountability. But this seems to be a difficult task giving the IRGC’s continued control of most of the economy’s key sectors.

Different Priorities

Iran announced a conservative state budget for the fiscal 2018-19 of about US$104 billion, which is about 6 percent increase from the budget plan for the current year. The new budget introduced cuts in social subsidies for some 30 million citizens while significantly increasing fuel prices.

The lifting of sanctions against Iran in January 2016, following the signing of the nuclear agreement, has contributed to a 16.3 per cent increase in the country’s GDP in 2016 thanks to increased oil exports. Nevertheless, the very slow-paced improvement in living standards disappointed the expectations of Iranians, where inflation is running at nearly 10 percent and unemployment is put at around 12.5 percent.

Ironically, the next public budget show increased government spending on religious institutions and the military. The government committed $853 million for Shiite institutions, representing a 9 percent increase from the previous budget, about double the funds committed to the ministry of culture. Military spending accounts for 20 percent of the 2018 budget ($22.1 billion), double the spending on education, healthcare and social care, while the IRGC alone received $7.7 billion and the regular army $2.5 billion.

The government does not consider military spending, which accounts for nearly 4 per cent of GDP, as unjustifiably high, especially because of ongoing conflicts across the Middle East. However, this does not negate the fact that many Iranians view this as seriously defective spending.

More Dilemmas

The budget not only implies gaps in spending on various sectors, but includes that the government's public accounts do not reflect the real fiscal performance of the public sector. The reason is that government activities account for no more than 17 per cent of the GDP, while the wider public sector, including the Bonyads and IRGC-affiliated institutions, account for 70 per cent.

Undoubtedly, failure to incorporate the accounts of many public institutions in the government's account does reflect the parliament’s weak oversight on the financial activity and operations of the public sector. On the other hand, relevant international institutions recommend a fiscal strategy built on merging all public accounts into one unified account to make it possible to assess the government’s fiscal position and ensure efficient financial control.

Lack of a unified account for Iran’s government operations is among the causes of rampant corruption throughout a majority of the economy’s sectors, which consequently weakened the government’s performance in providing services and implementing housing projects such as the failed Shandiz project which triggered popular protests in Mashhad City. Moreover, several banks in this city went bankrupt and their customers lost their savings.

Iran’s banking system suffers from the problem of non-performing loans, due to increased lending to IRGC-affiliated institutions at lower-than-market interest rates. This has weakened the quality of the banks’ financial assets and recently eroded the financial position of some of them.

Overall, some international institutions note that corruption and lack of transparency in Iran are among key causes of low living standards and deterioration of the investment climate, making Iran rank as one of the most corrupt countries scoring 131 points out of 176 on the 2016 Corruption Perceptions Index.

Hard Choices

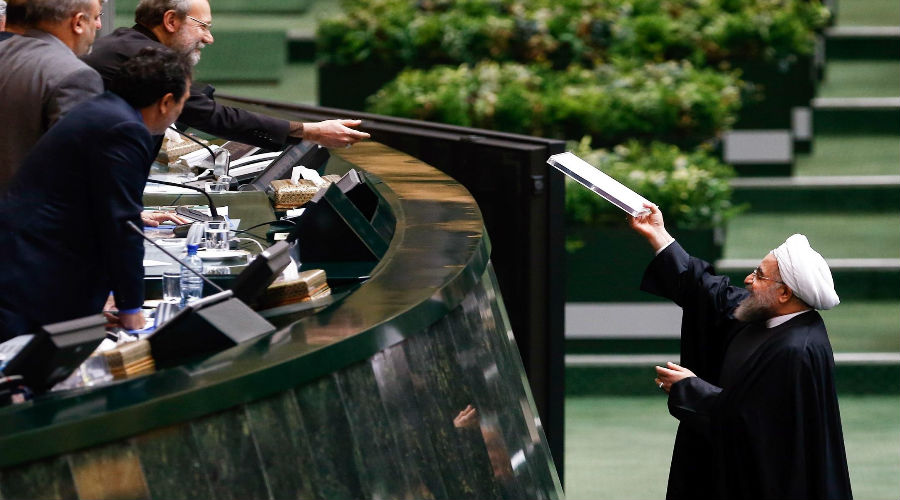

The Iranian regime appears to be forced to respond to the messages sent out by the recent popular protests. For one, it needs to mitigate domestic pressure it came under as tensions escalate with neighboring countries and international powers and the United States in particular. This forced the Iranian parliament’s economic committee to reject proposals from the government of President Hassan Rouhani, keep gasoline prices unchanged and ban any increase in customs duty and government service fees.

Perhaps the Iranian government can currently co-exist with this move and avoid bearing huge financial burdens. This is especially so because global oil prices went up to $65 a barrel making it possible to generate higher government revenue compared with the previous two years, and addresses a slight public budget deficit of no more than 3 percent in the past three years but is expected to rise to 2.3 per cent by the end of this year.

The Iranian government needs to introduce a trustworthy financial system incorporating a unified financial account that would enable the parliament to monitor economic operations of all government institutions, including the Bonyads and IRGC-affiliated companies. But the system appears to be difficult to achieve because the IRGC, and even the Bonyads, are excluded from having to be part of public accounts. This advantage allows these bodies to spend freely on military activity inside and outside Iran using revenues generated without any popular oversight and eventually consolidate their influence.

The major future challenge facing the government is to sustain a balance between military and social spending while also establish a unified governmental financial system to address deficiencies such as corruption and inefficient spending.