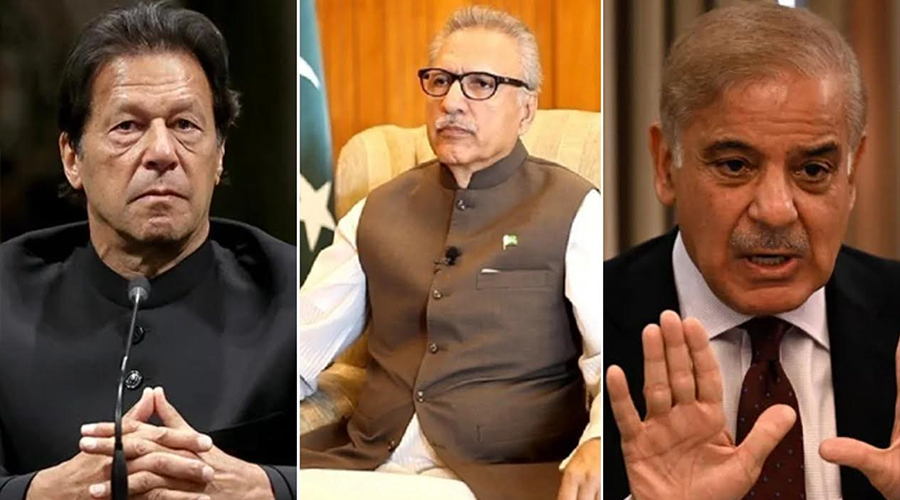

The political crisis in Pakistan continued to escalate over the past period to culminate, on the morning of April 10, in the Parliament’s withdrawal of confidence from ex-prime minister Imran Khan. The next day, the parliament approved opposition leader and current president of the Pakistan Muslim League Shehbaz Sharif as the new prime minister.

Especially after Khan claimed that the United States plotted to oust him because of his position on the war between Russia and Ukraine, this crisis cannot be separated from interactions, and conflicts and rivalry in particular, that are taking place on the international arena.

What triggered the escalation?

Ousted prime minister Imran Khan’s visit to Moscow on February 24, the day Russian forces invaded neighboring Ukraine, was the latest chapter in the rift between the United States and Pakistan, which practically developed during Khan’s tenure.

Islamabad started to sense that the United States’ interest in Pakistan was gradually dwindling, while showing increasing interest in India. But Islamabad has always had a strong interest in maintaining and promoting relations with the United States. Khan walked the same line, but did not manage to hide his criticism of what he called the United States’ inattention to his country and the sacrifices it offered as part of the war on terrorism. His criticism became even louder last year following the US withdrawal from Afghanistan. He spoke about US military operations inside Pakistan where, he said, caused thousands of casualties.

Khan made his visit to Moscow at a time when the US was escalating its rhetoric against Russia before its military intervention in Ukraine. The US has in fact attempted to cancel Khan’s Moscow trip, but its words went unheard in Islamabad because of Khan’s positions and the tensions already marring relations between the two countries.

Conspiracy allegations

Khan alleged that the US, which was not pleased with his government’s policies, has plotted to oust him from power. Khan went further to claim that there is a document from a US official that proves his claims of a foreign conspiracy. He even called what happened a stark intervention in the internal affairs of Pakistan and a plot against him and his government. Khan also claimed that the US used Pakistan’s domestic political arena to mobilize the opposition parties against him, and that its behavior has led to the parliament’s vote of no-confidence against him.

Defending Khan’s narrative of an American plot against him, the Russian foreign ministry, in a statement, accused the US of acting out of narrow interests and of “shameless interference” in the internal affairs of other states, and noted that Washington exert rude pressure on the prime minister, demanding an ultimatum to cancel the trip. When he refused to comply, Washington decided to punish him and all of a sudden a group of members of his own party Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf joined the opposition and the parliament was asked to hold a no-confidence vote against him. Moscow was well aware not to forget to reiterate its full preparedness to work with Islamabad based on full equality and mutual respect of the interests of both countries. The implication of Moscow’s statement for the US and its relations with Pakistan are evident enough.

For its part, the US, on several occasions, dismissed Khan’s allegations of conspiring against him, and emphasized that it is following the situation in Pakistan. It also reiterated that it respects the constitutional process and the rule of law and that it does not back any specific party against other parties. It also noted that it adopts this principle for dealing with all states and not only Pakistan.

China cannot afford to ignore the developments in Pakistan and its foreign implications for both Washington and Moscow. The Sino-Pakistani relations are at their best now. Ousted Pakistani prime minister Khan attended the opening ceremony of Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics, which Washington and some of its allies diplomatically boycotted. Khan’s move is perhaps what fueled Washington’s anger.

Khan did not stop at this. In a first for Beijing, the government invited China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi to attend the meetings of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation in Islamabad as a special guest. The US already imposed sanctions against China over rights abuses against the Muslim Uighur minority group. That is why the attendance of a Chinese official at a meeting of the organization, which defends Muslim minorities across the world, is viewed as a challenge to the US Administration.

Withdrawal of confidence

The Pakistani opposition demand for a no-confidence vote against Khan’s government was not immediately fulfilled by the parliament and held no sessions to discuss the request. Excuses for putting off the parliament’s sessions include that the country was hosting a meeting of the foreign ministries of members of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation.

Later the speaker of the parliament refused to initiate the no-confidence vote.

On April 3, President of Pakistan Arif Alvi, dissolved the parliament on advice from Khan, who also called for early elections. This, according to Khan, came as a surprise for the opposition, but what really surprised him is that the opposition went to the Supreme Court, which reinstated the previous situation and on April 7 ordered a no-confidence vote against Khan’s government.

When the parliament held a session, the question then was whether to immediately hold the no-confidence vote or wait until after discussions, and also how long should these discussions take?

Obviously, the speaker of the parliament sought to drag on discussions which heated up and the opposition was pressing for execution of the ruling of the Supreme Court that endorsed the no-confidence vote. After long hours of tensions, the speaker and deputy speaker of the parliament resigned.

The no-confidence motion, which required 172 votes to pass, was supported by 174 politicians, making Khan the first prime minister to be ousted through a parliamentary no-confidence vote in a country where no prime minister would complete the five-year term.

The parliament then, on April 11, elected Shehbaz Sharif, a brother of former prime minister Nawaz Sharif, as prime minister. He won 174 votes out of 342. All lawmakers from Khan’s party resigned in protest of the formation of a new government by his political opponents.

Potential trajectories

The major question revolves around the implications of ousting Khan’s government for Pakistan. These include interactions between Pakistan’s political forces, and Pakistan’s official positions, on one hand, and relations with the world powers and burning issues such as the war in Ukraine, on the other. The consequences of Khan’s removal from power can be outlined as follows:

1- The internal situation:

Although the opposition teamed up to join their ranks and oust Khan’s government, their unity may not hold for a long time. Disagreement can develop in the future after the election of Sharif as the new head of government. Perhaps, if Khan and his supporters continue to maintain presence in the political arena even after the ousting of Khan would help keep their opponents united as Imran’s own party, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, has now become opposition.

But would Khan keep calling his supporters to take to the streets? Or will he be content with being in institutional opposition? Would the parties that were accused of being involved in being part of a foreign conspiracy against the country’s government stop their bid after the ousting of the government and its head or they will seek to prosecute Khan and his supporters over these accusations? Regarding the next elections, would the new government complete its five-year term or will there be early elections?

Answers to these questions hinge upon many variables, including the way Pakistan’s political life will be run, and whether the interactions, which are still peaceful, will slip into tensions and maybe violence as each camp mobilizes their supporters and engage in clashes. Moreover, the economic situation will play a crucial role in the new government’s performance and popular satisfaction or dissatisfaction. That is why there are fears now that if tensions continue to grow and the economic situation worsens, the Pakistani army is likely to step in. However, other variables can factor in to prevent or ease economic and political tensions. These include success of the new government, which is more friendly to the West, in securing foreign loans and aid from states or international institutions. Additionally, pressure on the budget may slightly ease if the war in Ukraine comes to an end and global prices of Pakistan’s major imports begin to fall.

2- Islamabad’s foreign policy:

The pivotal question here revolves around the issue on which Khan judged the behavior of the opposition i.e. his disobedience to Washington, especially regarding the war in Ukraine. Would Pakistan change its position? Islamabad wants the Russian-Ukrainian war to come to an end, and calls for attention to humanitarian issues and a peaceful solution to the crisis. But Pakistan did not condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and abstained from a vote on UN resolutions condemning Russia, and of course did not join other states that imposed sanctions against Moscow.

Accordingly, it can be said that the new government led by Shehbaz Sharif will find it hard to bring about a change or a shift in Pakistan’s position on the Ukraine war because any change would become proof of Khan’s allegations of a foreign conspiracy against his government. This would corrode the legitimacy of Sharif’s government and even prompt its supporters both on the streets and inside the parliament to withdraw their support, which would make it to the undergo the same fate as Khan’s government. Moreover, Pakistan cannot afford to easily sacrifice its relations with Russia, because such a shift would raise fears in China. It should be noted that India took the same position on the Ukraine war as Pakistan, despite New Delhi’s strong and growing ties with Washington and western allies. These will become Islamabad’s instruments of leverage when it negotiates with Washington about its position on the Russian-Ukrainian war.