Although corruption is not a new issue for Latin American countries, the outbreak of corruption cases in the past few months has raised fundamental questions: Is corruption threatening political stability in the region? Will corruption kill the Latin American left? These revelations in recent months have become particularly worrisome when countries such as Argentina, Brazil, and Chile are the protagonists. These countries have usually performed better in terms of corruption indexes than other countries in the region, especially Chile, which was considered a paragon in Latin America. This article will focus on the aforementioned states, and how their involvement in the outbreak of corruption will affect the region's political stability.

Mapping Corruption in Latin America

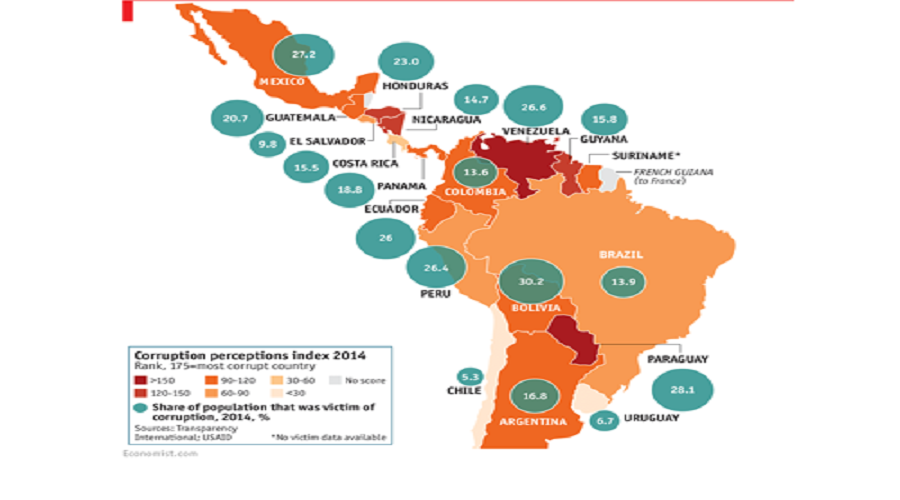

Two-thirds of Latin American countries are placed in the bottom half of Transparency International’s “Corruption Perceptions Index”[1]. Transparency International’s 2014 Report finds no major changes in Latin America’s corruption indices from previous years and argues that despite anti-corruption policies and reforms that suggest improvement on the surface, their implementation in reality is still lacking. Brazil and Mexico are cited as two major examples with crucial implications for the region given their influence as geopolitical leaders. In 2014, Brazil scored 43 and Mexico 35 in corruption perception indices. The main determinant of the former being the case of Petrobras, where public officials and private allies used billions of dollars from Brazil’s largest company for political parties’ financing. As for Mexico, the main determinant was the murder of more than 40 students in Iguala, which demonstrated the extent of corruption and criminality in the country.[2]

The recent outbreak of corruption cases involves countries from across the region, as documented by an article in The Economist. The scandal involving Petrobras in Brazil, the illicit enrichment of Argentina’s president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and her husband Néstor Kirchner and the accusations of corruption of Chile’s President Michelle Bachelet’s son constitute major cases in point.[3] In addition, The Financial Times reports on the outbreak of corruption cases in Mexico and Central America. In Guatemala, the government of Otto Pérez Molina is faced with a corruption scandal known as “The Line”, which refers to a phone number given to importers seeking to evade customs duties in exchange for bribes. Molina has recently resigned and been imprisoned amid these fraud charges. In Mexico, protests continue over the murder of 43 students in 2014, which likely involved corrupt police officers. In Honduras, President Juan Orlando Hernández is accused of controlling the judiciary, based on the Supreme Court’s elimination of the constitutional re-election ban in April. In El Salvador, President Salvador Sánchez Cerén has set up “four elite battalions” within the police and army to counter with force the violence by two powerful “mara” (criminal gangs) after more than 480 murders in March of this year.[4] The implications of recent corruption cases for the political stability of the region are particularly intriguing when relatively stable and well-performing countries, such as Argentina, Brazil and Chile are involved.

The Case of Argentina

Argentina scored 34 in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, ranking 107 out of 175 countries. In addition, 77% of the population feels the government’s efforts to fight corruption are ineffective and 62% feel that from 2007-2010 the level of corruption increased; while the institutions perceived to be most corrupt are political parties, which are rated 4.1 in a scale where 5 is extremely corrupt and 1 not corrupt, followed by the parliament and legislature with a 3.9 score. [5]

According to Transparency International, Argentina has adequate legislation aimed at preventing public sector corruption and a number of institutions tasked with fighting corruption; however, there is still a gap between anti-corruption measures and their actual enforcement.[6] One main area where corruption is often denounced is the funding of political parties and campaigns. Law 26.571, enacted on 2nd December 2009, introduces a reform to the political financing regulation aimed at increasing transparency.[7] In addition, law 26.683, enacted on 17th June 2011, defines money laundering as an independent offence from other crimes and specifies penalties that include prison terms of three to 10 years as well as the freezing and seizure of property.[8] Despite these measures, corruption continues to be observed in the political arena. Corruption is also denounced in the judiciary, which is characterized by lack of transparency and clear rules in the selection of judges as well as the absence of autonomy from the executive branch. [9] Recent cases put in evidence the prevalence of corruption in these areas.

The International Assessment and Strategy Center (IASC) issued a report in October 2014 on three corruption scandals involving the Kirchner government.[10] The former anti-drug chief Jose Ramon Granero was accused of facilitating the importation of massive quantities of ephedrine, a substance used in the production of methamphetamine. It is reported that the government has refused to turn over phone records requested by the judge overseeing the case, who has in fact accused the government of attempting to block the investigation. Argentina’s president has also been implicated in financial dealings requested by Judge Lazaro Baez, who is a financial associate and close friend of the Kirchners. It is reported that in 2011 alone, Baez moved about $65 million out of Argentina into overseas’ accounts and that the money in question appeared to be part of the president's personal fortune, which “inexplicably increased from $1.6 million to a declared $21 million during her administration and that of her late husband”[11].

Around the time of the former case, President Kirchner launched the “Legitimate Justice” initiative, which allows more involvement from the executive branch in judicial proceedings.[12] Finally, the third case involves Argentina's vice president Amado Boudou.[13] Boudou was prosecuted in June 2014 for corruption and abuse of power as he gained control of the company that printed the nation’s currency.[14] Boudou accepted a bribe of a 70% share in Ciccone printers in return for cancelling bankruptcy proceedings by Argentina's tax office and obtaining government contracts for printing the nation's banknotes.[15] The judge dealing with Boudou’s illegal enrichment and money laundering was removed and the prosecutor resigned.[16]

This year, the death of prosecutor Alberto Nisman on the 18th of January has awoken suspicions of the president’s involvement.[17] Nisman was the federal prosecutor charged with investigating the 1994 bombing of the Jewish community center, or AMIA, in Buenos Aires, which left 85 people dead and 300 more injured. Nisman planned to deliver evidence “linking the Argentine government to the Iranian regime in a pact to cover up Tehran’s role in the bombing” in the context of a “food-for-oil agreement” between Iran and Argentina.[18]

The Case of Brazil

Brazil scored 43 in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, ranking 69 out of 175 countries. In addition, 54% of the population feels the government’s effort to fight corruption are ineffective and 64% feel that from 2007-2010 the level of corruption increased; while the institution perceived to be most corrupt are political parties, which are rated 4.1 as in Argentina and the parliament and legislature are also rated 4.1.[19]

According to Transparency International, Brazil has some of the strongest anti-corruption regulations in the region but has been proved insufficient to deter corruption in practice. For instance, more than 1 million Brazilians signed a 2010 draft bill, which was passed as the “Clean Records Law” to prevent corruption in legislature. [20] In addition, since 2010, the electronic platform Transparency Portal allows Brazilians to track how public money is being used in all federal government programs and a law on right to information was passed in 2012 for Brazilian citizens to access federal, state, provincial, and municipal public documents. [21] However, public officials in Brazil have often been charged with demanding bribes and corruption cases continue to flourish in Brazil’s public administration.

From 2003 to 2012, the federal auditor’s office fired nearly 4,000 employees from public service due to corruption.[22] Influence peddling, the illegal practice of using one's influence in government to obtain favors or preferential treatment, is also prevalent in Brazil. In 2011, two members of Parliament were forced to resign and in 2012 the former head of the presidential office was dismissed by President Dilma Rouseff due to influence peddling.[23] In August 2012, in one of the biggest political corruption scandals, known as the Mensalão Scandal, 25 out of 37 defendants were found guilty for using public funds to buy political support in Parliament for President Lula da Silva’s government and to pay off debts from election campaigns.[24]

On March 6th of this year, the Brazilian Supreme Court agreed to open investigations into 34 sitting politicians, including the speakers of both houses of Congress, whom a prosecutor suspects of participating in the corruption case involving Petrobras, the state-controlled oil company, known as the Petrolão Scandal.[25] It is now known that at least 3 billion dollars have been stolen from Petrobras and that those implicated include members of president Rousseff’s inner circle, such as the Workers’ party treasurer João Vaccari as well as former president of Brazil Fernando Collor de Mello and the president of the senate Renan Calheiros.[26] Brazil’s president was Petrobras’ Chairman while the corruption cases took place, which has caused rallies across the country to demand her impeachment. [27] Some have argued that prosecutions in Brazil’s corruption cases demonstrate that politicians can be held accountable and ensures the credibility of the judicial system. [28] However, others have pointed out that the appeals process in Brazil’s legal system can be extended for decades and politicians, in particular, often appear to enjoy impunity. [29]

The Case of Chile

Chile scored 73 in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, ranking 21 out of 175 countries. In addition, 33% of the population feels the government’s efforts to fight corruption are ineffective and 53% indicate that from 2007-2010 corruption levels increased; while the institution perceived to be most corrupt are political parties, which are rated 4 and the parliament and legislature rated 3.7.[30]These indicators are significantly better than in the previous two cases. However, Chile’s high standing is being questioned as the administration of President Michelle Bachelet faces criticism for various corruption cases.[31]

In February 2015, the media reported that Bachelet’s son Sebastián Dávalos and daughter-in-law accessed a 10 million dollars loan from a prominent banker during the presidential campaign, which was used by a company partially owned by Bachelet’s daughter-in-law to purchase real estate and resell it, making millions of dollars in profits.[32] In March 2015, business executives from the financial group Penta were arrested on charges of tax evasion and accused of using fake receipts to illegally finance the campaigns of candidates for the opposition Independent Democratic Union party.[33] President Bachelet has consequently announced a number of anticorruption measures and the intention to rewrite Chile’s constitution in order to tackle corruption, which starts this month. Earlier in May 2015, the political situation in Chile took a turn as Bachelet named a new cabinet, including the replacement of her cabinet chief Rodrigo Penailillo and the Finance Minister Alberto Arenas, and the Ministers of Justice, Defense, Labor, Culture and Social Development.[34]

Concluding Remarks

The outbreak of corruption cases across Latin America in the past few months, particularly in Argentina, Brazil and Chile, has to some extent threatened the political stability in the region and has significantly decreased the popularity of the left. At the same time, it has encouraged civil mobilization, the prosecution of public officials and the adoption of new and radical measures against corruption, such as Chile’s cabinet removal in May 2015. Some have argued that “the viceroys of the colonial era set the pattern”, with centralized power and the loyalty of local interest groups facilitating corruption; while others have taken the prosecutions of public officials as good symptoms of these democratic systems in fighting corruption. [35]Despite widespread public mobilizations, political stability in these countries seems so far to prevail. It will only be in the next round of elections that the future of the left will be decided. This future may be hinted at by Argentina’s upcoming elections in October this year.

[1] The Economist Data Team, “A less crooked continent?” The Economist, March 16, 2015,http://www.economist.com/blogs/graphicdetail/2015/03/daily-chart-7 (accessed May 18, 2015). The corruption perception index is a composite index, drawing on corruption-related data from expert and business surveys carried out by a variety institutions. Scores range from 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean). See http://www.transparency.org.

[2] Alejandro Salas, “Corruption in the Americas,” Transparency International, December 3, 2014,http://blog.transparency.org/2014/12/03/corruption-in-the-americas-the-good-the-bad-and-the-ugly/(accessed May 18, 2015).

[3] The Americas, “Democracy to the rescue?” The Economist, March 14, 2015,http://www.economist.com/news/americas/21646272-despite-epidemic-scandal-region-making-progress-against-plague-democracy (accessed May 18, 2015).

[4] Jude Webber, “Past comes back to haunt Latin American leaders,” Financial Times, May 4, 2015,http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/282d3ca6-f249-11e4-b914-00144feab7de.html#axzz3aVgRNycH (accessed May 18, 2015).

[5] Transparency International, Argentina, https://www.transparency.org/country#ARG_PublicOpinion(accessed May 18, 2015).

[6] Ibid.

[7] Argentinean Government, Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas Públicas, Law 26.571,http://infoleg.mecon.gov.ar/infolegInternet/anexos/160000-164999/161453/norma.htm (accessed May 18, 2015).

[8] Ibid,http://www.infoleg.gov.ar/infolegInternet/anexos/180000-184999/183497/norma.htm (accessed May 18, 2015).

[9] Transparency International, Argentina, https://www.transparency.org/country#ARG (accessed May 18, 2015).

[10] Kyra Gurney, “Argentina Embroiled In Narco Corruption Scandals: Report,” InsightCrime: Organized Crime in the Americas, October 31, 2014, http://www.insightcrime.org/news-analysis/argentina-narco-corruption-scandals-report (accessed May 18, 2015).

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Jonathan Gilbert, “Argentina’s Vice President Charged in Corruption Case,” New York Times, June 28, 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/29/world/americas/argentine-official-charged-with-bribery.html?_r=0 (accessed May 18, 2015).

[15] Uki Goni, “Cristina Fernández de Kirchner under pressure after vice-president charged,” The Guardian, June 29, 2014, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jun/29/argentina-vice-president-amado-boudou-cristina-fernandez-de-kirchner (accessed May 18, 2015).

[16] Transparency International, Argentina, https://www.transparency.org/country#ARG (accessed May 18, 2015).

[17] Jeremy Adelman, “Why It’s So Hard to Know the Truth in Argentina,” The Slate Group, February 9, 2015,http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/foreigners/2015/02/alberto_nisman_s_mysterious_death_and_president_cristina_fern_ndez_de_kirchner.html(accessed May 18, 2015).

[18] Jeremy Adelman, “Why It’s So Hard to Know the Truth in Argentina,” The Slate Group, February 9, 2015,http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/foreigners/2015/02/alberto_nisman_s_mysterious_death_and_president_cristina_fern_ndez_de_kirchner.html(accessed May 18, 2015).

[19] Transparency International, Brazil, https://www.transparency.org/country#BRA (accessed May 18, 2015).

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] BBC News, “Brazil's 'big monthly' corruption trial,” BBC News, November 16, 2013,http://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-19081519 (accessed May 18, 2015).

[25] The Americas, “Democracy to the rescue?” The Economist, March 14, 2015,http://www.economist.com/news/americas/21646272-despite-epidemic-scandal-region-making-progress-against-plague-democracy (accessed May 18, 2015).

[26] Jonathan Watts, “Brazil elite profit from $3bn Petrobras scandal as laid-off workers pay the price,” The Guardian, March 20, 2015, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/20/brazil-petrobras-scandal-layoffs-dilma-rousseff (accessed May 18, 2015).

[27] The Americas, “Democracy to the rescue?” The Economist, March 14, 2015,http://www.economist.com/news/americas/21646272-despite-epidemic-scandal-region-making-progress-against-plague-democracy (accessed May 18, 2015).

[28] Ibid. And BBC News, “Brazil's 'big monthly' corruption trial,” BBC News, November 16, 2013,http://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-19081519 (accessed May 18, 2015).

[29] Jonathan Watts, “Brazil elite profit from $3bn Petrobras scandal as laid-off workers pay the price,” The Guardian, March 20, 2015, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/mar/20/brazil-petrobras-scandal-layoffs-dilma-rousseff (accessed May 18, 2015).

[30] Transparency International, Chile, https://www.transparency.org/country#CHL (accessed May 18, 2015).

[31] Helena Ball, “Undoing the evils of corruption in LAC,” Panam Post, April 27, 2015,http://panampost.com/helena-ball/2015/04/27/undoing-the-evils-of-corruption-in-latin-america/ (accessed May 18, 2015). And Malgorzata Lange, “Corruption in Politics: Chile’s Gordian Knot,” Panam Post, April 20, 2015, http://panampost.com/malgorzata-lange/2015/04/20/corruption-in-politics-chiles-gordian-knot/(accessed May 18, 2015).

[32] Ryan Dube, “Chile’s President Vows to Tackle Corruption, Rewrite Constitution,” The Wall Street Journal, April 29, 2015, http://www.wsj.com/articles/chiles-president-vows-to-tackle-corruption-rewrite-constitution-1430321012 (accessed May 18, 2015).

[33] Ryan Dube, “Chile’s President Vows to Tackle Corruption, Rewrite Constitution,” The Wall Street Journal, April 29, 2015, http://www.wsj.com/articles/chiles-president-vows-to-tackle-corruption-rewrite-constitution-1430321012 (accessed May 18, 2015).

[34] The Guardian, “Chilean president names new cabinet in move to overcome scandals,” The Guardian, May 11, 2015, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/may/11/chilean-president-names-new-cabinet-revive-popularity (accessed May 18, 2015).

[35] The Americas, “Democracy to the rescue?” The Economist, March 14, 2015,http://www.economist.com/news/americas/21646272-despite-epidemic-scandal-region-making-progress-against-plague-democracy (accessed May 18, 2015).