US-based oilfield services group Halliburton said on September 14 that it was awarded a contract to drill as many as five wells off the coast of Israel. Halliburton, which will conduct the work for London-based Energean, will deliver all services including project management, production enhancement, and subsea services. Halliburton previously executed a four-well campaign at Energean’s Karish and Karish North gas fields offshore Israel.

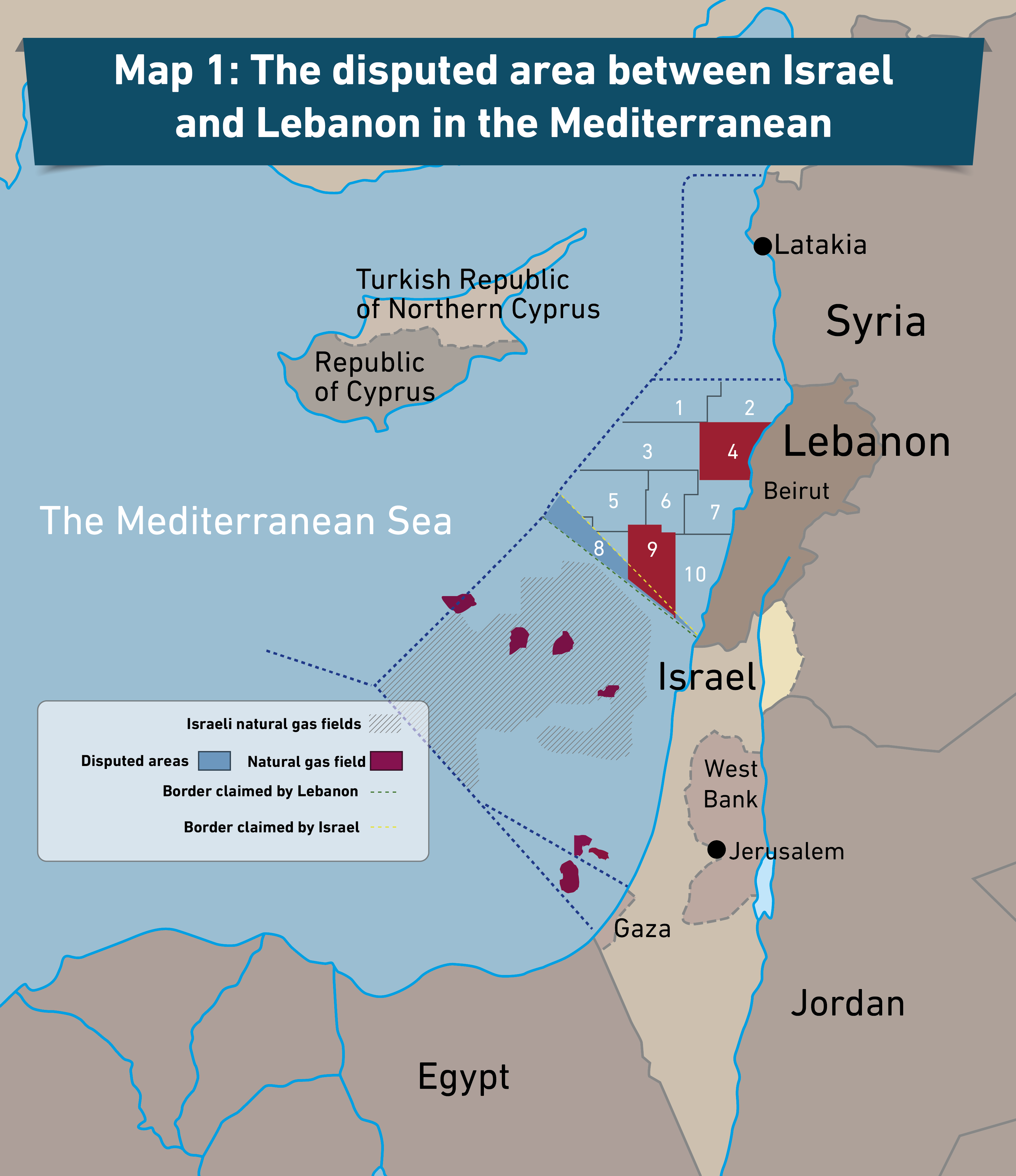

A part of the Karish gas field is located in the disputed maritime border with Lebanon (See Map 1), but it is still unknown whether Halliburton’s contract includes work in the disputed area. This prompted Lebanon’s permanent representative to the UN, Amal Mudallali, to submit a letter to both UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres and Ireland's delegate to the UN, Geraldine Byrne Nason, the current president of the UN Security Council, on the matter. Mudallali called on the UNSC to "ensure that the drilling evaluation works are not located in a disputed area between Lebanon and Israel, in order to avoid any attack on Lebanon's rights and sovereignty” and to "prevent any future drilling in the disputed areas and to avoid steps that may pose a threat to international peace and security."

Implications of Israel’s move

It should be noted that Israel’s swiftly moved at this time to accelerate the exploitation of natural gas resources in the disputed area with Lebanon due to the following reasons:

1- Taking advantage of Lebanon’s economic crisis:

Israel’s move is aimed at pushing Lebanon to go back to the US-mediated negotiations at a time when Lebanon is going through an economic crisis. Currently, the government led by Najib Mikati is focused on overcoming the crisis.

Development of maritime oil and gas fields will allow Lebanon to achieve energy self-sufficiency, and provide income from any exportable surplus. A report issued by Fransbank in July 2017 showed that there is nearly 1.7 billion barrels of technically recoverable oil and 122 trillion cubic feet of technically recoverable gas in the Levant Basin, of which part of each is found in Lebanon, estimated at USD254 billion, two times and a half the amount of Lebanon’s public debt which reached USD97 billion in late April 2021, according to data released by the central bank of Lebanon.

2- Pressuring Lebanon to return to negotiations:

Former US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, in a visit to Lebanon in March 2019, succeeded in reviving the stalled negotiations between Israel and Lebanon. Four rounds of talks were held between the two countries from October 14, 2019 to early December 2020. In October 2020, the talks resulted in an agreement between Lebanon and Israel to a framework for the talks aimed at drawing up their maritime border. The fifth and last round of talks was held in April 2021.

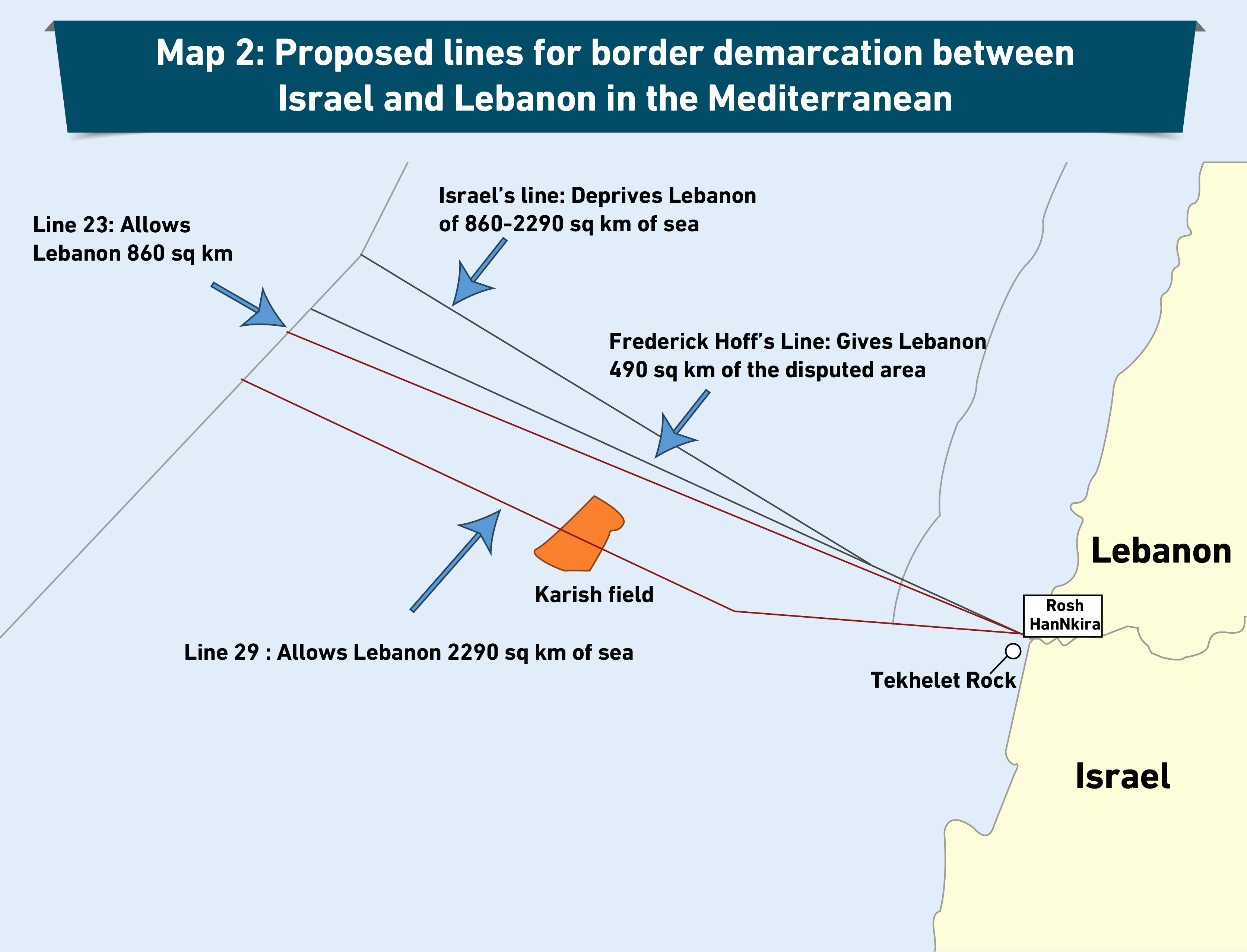

The fifth round of talks was supposed to discuss an area of 860 square kilometers of the Mediterranean Sea, based on a map sent to the United Nations in 2011. In the map, Lebanon claimed its border according to Point 23, agreed through a committee with members from Hezbollah and the Free Patriotic Movement led by President Michel Aoun. Later, Lebanon said that the map was based on wrong estimates and claimed an additional area of 1430 square kilometers that includes parts of the Karish field in which a Greek company is working on behalf of Israel. Lebanon’s proposal became to be known as Line 29 (See Map 2). Israel accused Lebanon of obstructing the talks by claiming an expanded disputed area, especially because that line will run through a part of Israel’s Karish field within Lebanon’s maritime border.

3- Attempting to impose a fait accompli:

Israel perceives three options for Lebanon to deal with the crisis. They are the US mediation, which continues to date although the talks between Lebanon and Israel stopped on April 5, 2021; seeking a settlement to the maritime dispute through an international arbitration committee; or referring the issue to the International Court of Justice, which requires agreement from both Lebanon and Israel.

The attempts might well result in nothing more than a waste of time, at a time when Israel is working on imposing a fait accompli by continuing drilling and production operations. This is especially so because a consortium made up of France’s Total, Italy’s ENI and Russia’s Novatek has not yet started exploration in Bloc 9, on the Lebanese side of the maritime border, which is several months behind schedule. The southern border of this block is the cause of dispute between Israel and Lebanon.

4- Preempting Mikati’s Moves:

Israel recognized the importance of preemption through placing pressure on the new Lebanese government whose statement provided for resumption of talks to protect Lebanon’s maritime border. The move is aimed at preventing renewed discussion of amending Decree No. 6433 which adopted Line 29 instead of Line 23 for demarcating the maritime border with Israel.

Tel Aviv categorically rejected the move. The development prompted the then-US Under Secretary for Political Affairs David Hale to visit Lebanon in April 2021 to pressure President Aoun away from approving Decree No. 6433. President Aoun gave in, especially because approval of the decree would spark a constitutional crisis. That is, amending the decree requires the government to hold a meeting to give its approval, which then was not possible because a caretaker government was running the country. Now, however, the Mikati government can pass this decree.

Lebanon’s three options

Beirut has three options for responding to Tel Aviv’s recent agreement with Halliburton. These can be outlined as follows:

1- Engaging in US-brokered negotiations:

The United States can step in again to pressure both countries to stop mutual escalation, especially because it is not clear yet whether Halliburton will work in the disputed area or not. Washington might also place pressure on both Lebanon and Israel to resume direct talks.

2- Diplomatic Escalation through the United Nations:

Such a move would not yield any results, especially because there are assessments reflecting a belief that Halliburton’s drilling operations will be kept away from the disputed area (according to Line 23). Therefore, submitting a complaint to the United Nations will only yield routine resolutions urging Lebanon and Israel to engage in negotiations to resolve their border dispute through peaceful means. Moreover, there will be no obligation for Tel Aviv to stop foreign companies from operating close to its coastline. But even if Lebanon amends and submits Decree No. 6433 to the United Nations, and proves that Halliburton is operating in a disputed area, this issue will have to be settled either through US-mediated negotiations, an international arbitration committee or the International Court of Justice.

3- Lebanon’s pressure on foreign companies:

Lebanon’s successive governments failed over the years to benefit from the oil and gas resources in the Mediterranean, although Lebanon signed an agreement with the Total-ENI-Novatek consortium in February 2018 for oil and gas exploration in Block 9, the southern part of which lies in the contested area with Israel.

In response to Israel’s awarding of drilling contacts, Speaker of Lebanon’s Parliament Nabih Berri accused the international consortium of failing to begin drilling and exploration operations so as Lebanon can benefit from its oil and gas resources and prevent Israel from imposing a fait accompli on Lebanon.

To conclude, the timing of Israel’s move to renegotiate the maritime border dispute with Lebanon, reflects Tel Aviv’s willingness to finalize the border demarcation with Beirut, and push the United States to pressure Lebanon to sit at the negotiating table with Israel over Line 23 instead of Line 29. Moreover, from an Israeli viewpoint, the deterioration of Lebanon’s economy will guarantee that this goal will be achieved, especially because the involved international companies operating in Lebanon have not yet launched development operations in Block 9.