Lebanon’s care-taker government, on August 21, decided to end fuel subsidies and import the commodity at a new exchange rate of 8000 Lebanese pounds to the dollar, about double the previous rate of 3900 pounds. The move comes as an initial step towards economic reforms and put an end to the subsidy policy upheld by the country’s successive governments.

The move was taken amid the government’s endeavor to ease the burden of heavy financial commitments and prevent the currency reserve from further drying up as a result of fast-diminishing foreign currency.

The decision, however, will inevitably impose further burden on the Lebanese as it sends the cost-of-living soaring.

Surprise Decision

On August 12, Lebanon’s Central Bank announced a decision - which it later reversed- that it would offer credit lines to fuel importers based on the market price of the Lebanese pound, with the exchange rate in the parallel market in recent days topping 20,000 pound. The August 12 decision, however, meant that the fuel subsidy will be suddenly ended.

The Central Bank, in a statement, said that it would go back to the previous exchange rate of 3900 pounds only if the parliament issues a legislation allowing it to use the mandatory currency reserve, estimated at USD14 billion. The bank is unlikely to accept such a decision under any circumstances because it is highly serious.

Financial and monetary circumstances that prompted the Central Bank to take the move can be outlined as follows:

1- Foreign currency reserve drying up:

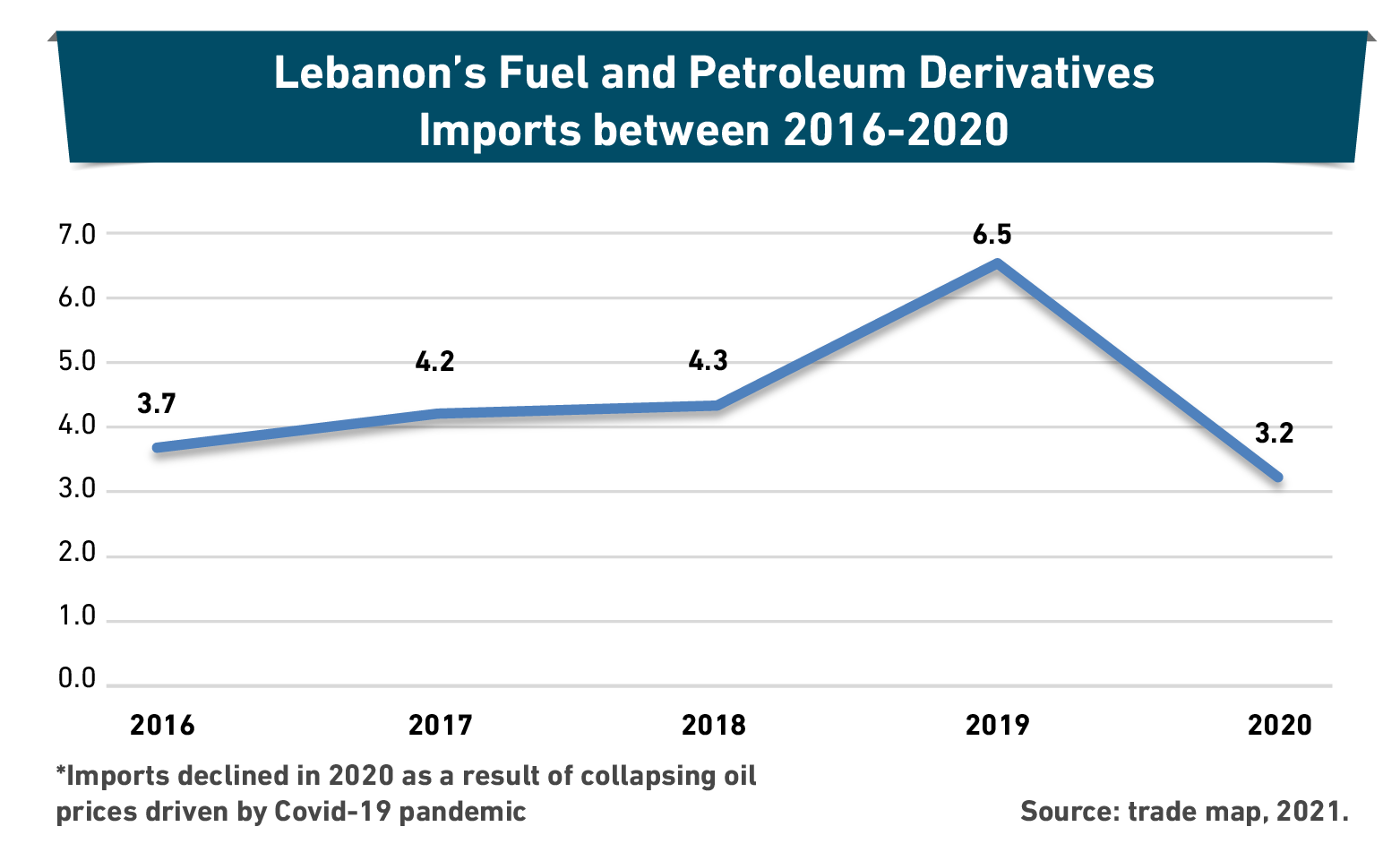

The policy of subsidizing essential commodities, including fuel, medicine and wheat, is based on fixed market prices and a preferential exchange rate for imports that is lower than the market price. It led to doubling up withdrawals from the Central Bank’s foreign currency reserve, amid high foreign debts and due interest payments owed by the government. The foreign currency reserves were USD23.3 billion in February, posting a 35.6 per cent year on year decline.

2- Danger of using the mandatory reserve:

The Central Bank maintains that, amid a drying up of foreign currency reserves, it is dangerous to dip into the mandatory reserve, which is a percentage of private banks’ foreign currency deposits, because it is meant to be the last resort for bolstering the financial position of both the bank and the state. Lebanon’s effective laws ban the use of this reserve without a legislation approved by the government.

3- Stopping the waste of government subsidies:

A significant part of government subsidies goes to ineligible individuals. Lebanese government officials confirmed that large amounts of subsidized fuel are smuggled to Syria through illegal border crossings to make profits from the difference in market prices in the two countries.

Partial Floating

The Central Bank’s decision to end all fuel subsidies surprised all Lebanon’s politicians, including the Lebanese Presidency and the caretaker cabinet led by Hassan Diab, who rejected the move. It also surprised political movements representing Lebanon’s sects who said it will inevitably cause a collapse of living conditions amid the country’s grinding economic crisis.

The Lebanese government, as well as the various political movements, say the decision is untimely, ignores the social and livelihood crisis already hitting Lebanon and preempts any compensatory measures to help out fragile segments likely to bear the brunt of fuel price rise. The caretaker government was planning to launch a ration card program injecting cash assistance for the most vulnerable families to ease the repercussions of ending subsidies on essential commodities.

The Lebanese presidency had to summon Central Bank governor Riad Salameh to hold consultations about his decision which sparked popular protests which saw angry citizens blocking roads. Lebanese President Michel Aoun held an emergency meeting with Salemeh in the presence of ministers of finance and energy to review the decision.

Wide popular protests and criticism from politicians, the Central Bank backed down, reversing the new policy for floating the exchange rate for imported fuel, and reached a settlement with the government on August 22.. As per the agreement, the Central Bank will cover urgent subsidies for fuel offering credit lines for fuel imports based on a fixed exchange rate of 16500 pounds to the dollar, while the government sells the fuel in the market at an exchange rate of 8000 pounds and pays the difference between the two rates. The bank will set aside up to $225 million to subsidize the imports for one month, until the end of September.

Likely Repercussions

The decision to remove a part of the government fuel subsidy is less harmful for citizens than ending all subsidies and leaving prices floating according to market dynamics and conditions. It will, however, cause negative economic repercussions, of which the following stand out:

1- Record fuel price hike:

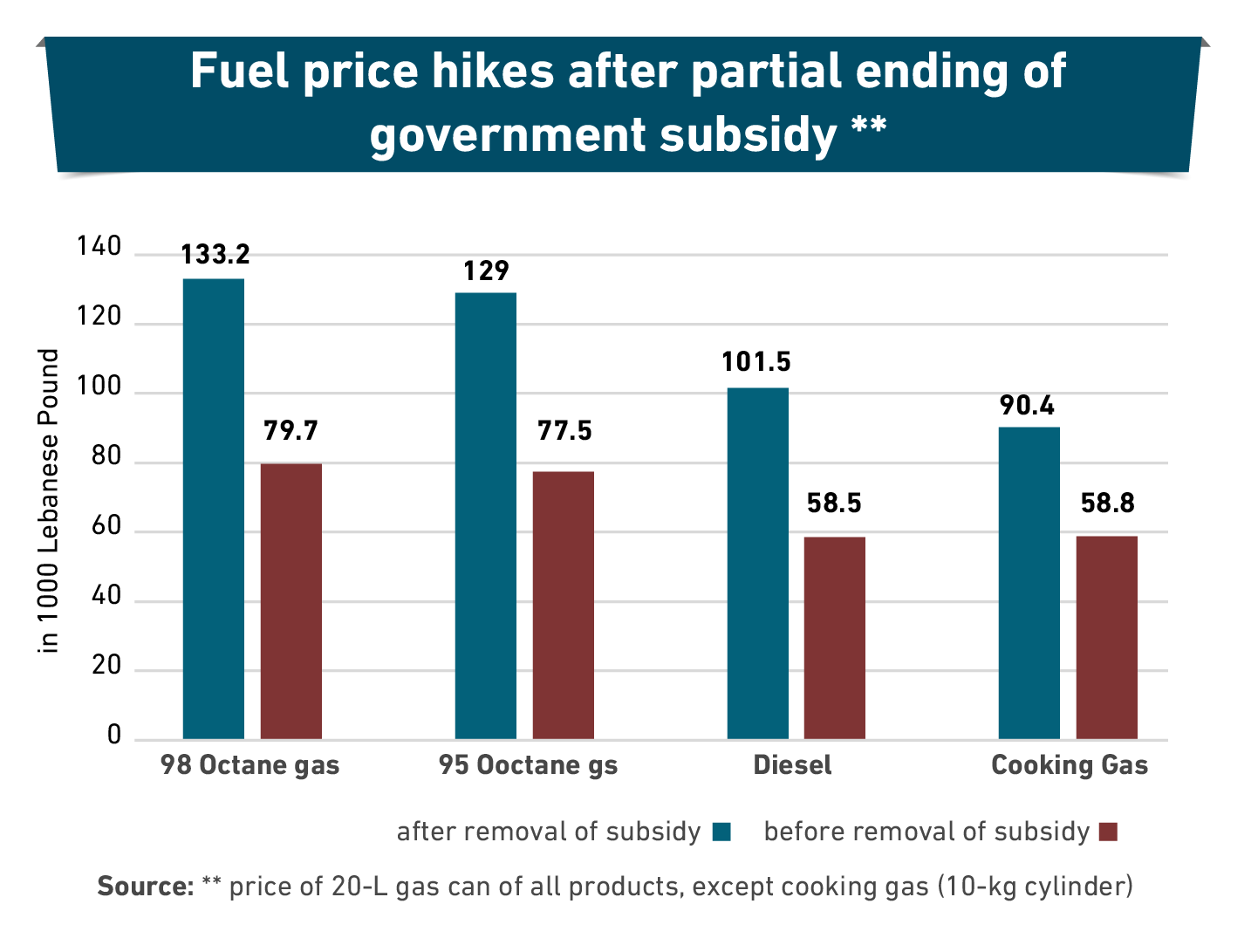

Prices of gasoline, diesel and cooking gas rose between 53-73 percent after the partial removal of government subsidy, and are likely to soar even higher in the black market, which spread across Lebanon in recent months due to fuel shortages.

2- Increasing prices of commodities and services:

The fuel price hike is expected to drive a parallel increase in the cost of transportation of goods and passengers, which will in turn cause a rise in prices of commodities and services. That is, more surges in inflations are expected. Last year the inflation rate went up to 84.9 per cent in 2020.

3- Higher poverty rate:

Ending government fuel subsidy imposes new financial burdens on Lebanese citizens already reeling under difficult living conditions. As a result, a wide segment of citizens was kept below the poverty line, while the overall number of the poor reached 55 percent in 2020, up from 28 percent in 2019, according to data from the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA).

4- Government financial burdens:

The decision will no doubt ease the financial burdens of the government and will slow down the fast-paced drying up of foreign currency reserves at the Central Bank. Despite this, the optimum course of action to bring public finance under control is to remove all fuel subsidy, which costs about USD3 billion every year, or half of government funds dedicated for subsidizing essential commodities.

Total Floating

Amid the current political and economic situation, the caretaker government may not be able to remove all fuel subsidy, but the decision will always be on the mind of Lebanon’s decision makers in the near future. The implementation of such decision hinges on the following dynamics:

1- Economic reform program:

The best way to get out of the current economic crisis is to form a new government that realizes the need and inevitability of economic reform, and prioritize relevant plans. The World Bank views reluctance to implement reform policies, including ending subsidies for essential commodities, threatens to cause further deterioration in Lebanon. Lebanon’s state partners would offer emergency financial aid to Lebanon only if the country could introduce a program for economic reforms.

2- Meeting market demand:

Sufficient fuel supplies on the market supports any government in power that plans to make a decision ending fuel subsidy. In other words, sufficient supplies would bolster the Lebanese’ confidence in the integrity and credibility of any measure aimed at ending fuel subsidies and prevent a parallel black market from emerging.

Sufficient fuel supplies can be secured from two sources:

a) Tapping local resources:

Providing fuel supplies requires the Central Bank to guarantee sufficient funding for fuel imports, which is uncertain due to the apex bank’s policy of preserving foreign currency reserves which are rapidly drained out.

b) Regional and international aid:

A new Lebanese government can hold talks with the country’s international partners about an emergency foreign currency aid package to fund major imports or to get fuel aid according to a short-term program.

3- Closing in on the black market:

The Lebanese government should join hands with the army forces to surround the black market at home and cross-border fuel smuggling so as to stabilize the market and prevailing fuel prices.

In conclusion, the next Lebanese government is expected to pursue a policy whereby it removes all fuel subsidy, but this will require it to meet several conditions including providing sufficient fuel supplies on the market, closing in on the black market as well as following a gradual course for ending the subsidy to empower all segments of the population to bear the consequences in the future.