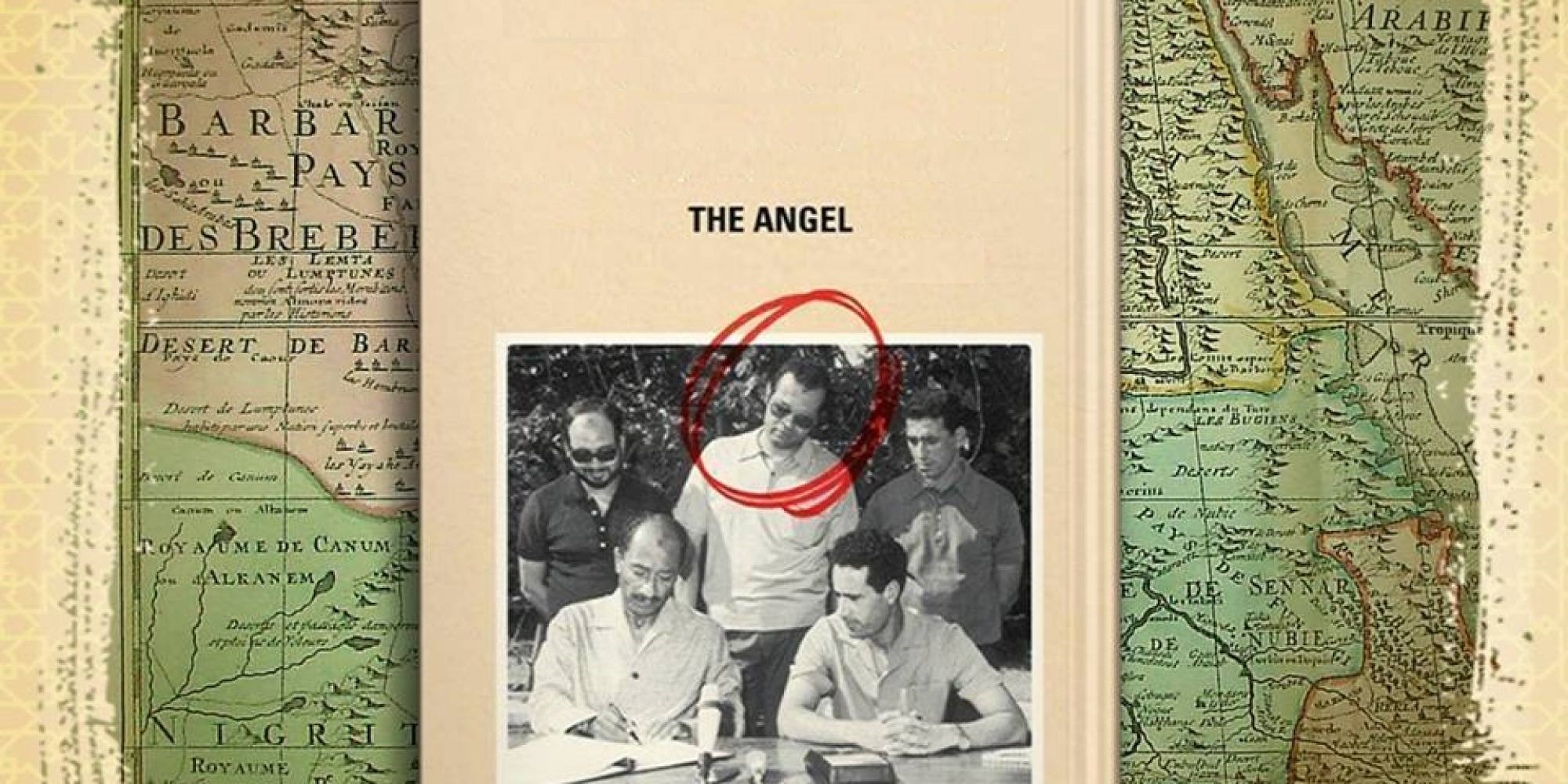

The curious case of Ashraf Marwan, the husband of Mona, daughter of former Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, continues to attract the attention of Israelis, as well as Egyptians and Arabs after Uri Bar-Joseph’s “The Angel: The Egyptian Spy Who Saved Israel” came out amid continued debate over the controversial figure considered by Zvi Zamir, the Mossad Chief, as a loyal individual who disclosed to the Israelis accurate intelligence to the Israelis including the timing of the October 1973 War against Israel was imminent.

But Eli Zeira, the director of Israel’s Military Intelligence in the 1973 War and the main culprit in the intelligence fiasco prior to the war, insists that Marwan, operating then under the Mossad code-name "The Angel, was a double spy who was well-handled by Egypt and deceived the Israelis and even causing their defeat in the war. The two men took to court in 2005, when Zamir accused Zeira of revealing Marwan’s identity in 1993 to newspapers, academics and researchers. The case was closed in 2012 sparing Zeira official indictment.

“The Angel” revives the case once again showing a clear bias in favor of Mossad by claiming that Marwan was a Mossad agent and not a double agent, rejected suggestions that he committed suicide and claimed that he was killed by the Egyptian intelligence.

War of Conflicting Accounts

Bar-Joseph is a well-known professor of international relations at Haifa University, and a specialist in national security, intelligence studies and the Arab-Israeli conflict. Which is the very reason why his book sounds like a weird and suspicious account of the story that looks more like a journalistic report citing weak sources such as newspapers, magazines and personal meetings with relevant people. The aim is to give more credibility to the story. The author even claims that he read four big volumes about Marwan that are kept by the Mossad’s archive.

Bar-Joseph’s treatment of his postulations on which he founded these conclusion reveal a great deal of conflicting information, assessments and readings that does not reflect his stature as a renowned academic in Israel. He even does not appear to be aware of the negative picture he presented to the Mossad. His book shows that Marwan’s Mossad handlers committed violations of basic professional rules that no intelligence agency would tolerate.

Debunking the Double-Spy Theory

The author began his book by rejecting the old story leaked to London-based Israeli historian Ahron Bregman during meeting with Eli Zeira in mid 1990s. This narrative claims that Ashraf Marwan went to the Israeli Embassy in late 1968 to offer his services to the Israelis. Bar-Joseph knew that such as story full of holes is not credible. How a well-known man like Marwan, then a staffer at the Egyptian Embassy, can go to the embassy of his country's enemy number one without planning, hiding and cheating while knowing that the Israeli Embassy must be under heavy surveillance from more than one party, including the intelligence agencies of Egypt, Britain and great powers.

To amend the narrative, Bar-Joseph claimed that Marwan did not go to the Israeli embassy but contacted it in early 1970 and again five months later. In both times, his calls were answered by the Israeli military attache (who was replaced later). Unknowing that Marwan was the son-in-law of the Egyptian president, both attaches could not see why Marwan should be an important figure. The author claims that Israel would have missed this opportunity had it not been for a stroke of bizarre chance that in later 1970 Mossad officials heard the story of the Egyptian who wants to help Israel.

In January 1970, the two Israeli officials called Marwan on a phone number that he gave to the Israeli military attache. At a London hotel, where the meeting was held, Marwan gave two Mossad agents - one of them was named Dubi- what was supposed to be top-secret information about the Egyptian army. Dubi’s colleague who ascertained that the secret documents were authentic, asked Marwan to provide, in a second meeting, answers to certain questions about Egypt’s military plans, order of battle and type of equipment and whether or not President Anwar Sadat was planning to carry out his threats to wage a war on Israel.

Later, in April 1971, after handing over the required information to the Mossad, Marwan was approved to be a agent for Israel. But due to several logical contradictions, this story cannot be easily accepted. Because he was supposed to be kept under a watchful eye by several parties, it was easy to expose Marwan during his visit to the Israeli embassy or at those meetings at the hotel.

Moreover, the two Mossad agents violated the strict rule of not accepting offers from walk-ins or volunteers because taking the risk would raise the possibility that Marwan is a double agent used by another intelligence agency. Another rule that was violated is that Mossad agents should not deal with any requests without prior permission from their leaders, which the two Mossad agents did in London, according to the author.

Bar-Joseph says that it took Israel only seven months - between Marwan’s first meeting with the Mossad agents and the Mossad’s approval to name him a new agent- to verify that he was not a double-spy used by the Egyptian intelligence. Mossad settled the debate rejecting this possibility, and decided to deal with Marwan code-naming him “the Angel”, on the grounds that the information he offered was credible, unprecedented and true when verified and compared with information from other sources.

An obvious contradiction pops up here: How can Marwan’s information be excellent and at the same time were verified by other sources?

Bar-Joseph notes that Marwan, up to 1997, insisted on refusing to meet any Mossad agent other than Dubi. And it was only after considerable pressure that Marwan agreed to meet an agent of the Israeli Military Intelligence. It was Marwan who decided the timing of his meetings with Dubia. During all these years, the Mossad did not record the conversations between Dubi and Marwan. Later, in 1997, when the Mossad claimed that it has such recordings, Marwan decided to severe all his ties, for good.

The claims made by the author do not show an agent who was controlled by the Mossad. Only a man of unusual capabilities can do the opposite, decides when the agents can meet him and threaten to end cooperation with them when the Mossad wants to change his handler. When the Mossad threatened him with recordings, this agent is not afraid of being exposed and decides to cut all contacts.

Bar-Joseph’s portrayal of the relationship between the Mossad and Marwan does raise questions: Who had the final say about this relationship and could decide when it should begin and when it should be cut? Which side recruited the other? How come the Mossad violated a traditional rule that no recruitment should be made without guaranteed means of control.

More importantly is Bar-Joseph’s acknowledgement that Marwan, since 1972, told Israel about three incorrect dates of the start time of the October 1973 War. He even asked for a meeting with the Mossad agents on the evening of October 4, 1973 (two days before the war broke out), using an agreed code word meaning that there is general talk about a war that can break out, and not the code word that means the hostilities were imminent.

The author claims that Marwan used of the wrong code word for war because he was afraid and confused.

Zamir flew to London to know the reason why Marwan gave a general warning without specifying the level of urgency. Marwan told him that the outbreak of hostilities would take place at 6 pm on October 6, 1973, but the information turned out to be incorrect and that Marwan used speculations after the Soviets had begun an emergency airlift of the families of their advisers in Cairo on the evening of October 4.

This shows that Marwan did not know the exact start time from President Sadat. Moreover, he is suspected of deliberating making two mistakes. Firstly, he used inaccurate code words and Israel did not know that hostilities were imminent. Secondly, when he set the precise date, he gave the wrong start time.

Rejection of the Suicide Theory

Bar-Joseph also dismissed the theory that Marwan took his own life saying that he has no family history of suicide, and that Marwan did not have depression before he died. To prove his claim, the author resorted to broad psychology to conclude assumption that Marwan killed himself can only be validated if he had a family history of suicide, was shocked because of his working or family relationships or friendships. However, some people may commit suicide although they have not gone through such experiences.

Many people who were close to Marwan, including his wife, emphasize that he was depressed and scared and often said that his life was in danger because the Mossad decided to liquidate him after it confirmed that he misled it. This situation can push an individual battling terminal cancer with little hope of a cure while Israeli newspapers continued to publish leaks about his personal life, to develop depression and even kill himself to escape these pressures.

More unusual still is Bar-Joseph’s claim that the Mossad tried to protect Ashraf Marwan since 1997. But Israeli newspapers continued to publish information that eventually led the disclosure of his identity in 2002. So how this claim be consistent with the fact that the Israeli Military Censor bans the publication of any information regarding the military and the security of Israel without prior permission?

But Who Killed Ashraf Marwan?

Bar-Joseph uses a weak logic to debunk the suicide theory. He rejects the possibility that Marwan’s business partners (in arms trade which Marwan left several years before his death) killed him over financial disputes, but then claims that no rivals were enemy. Which leaves us with two possibilities: Ashraf Marwan was killed by either the Mossad or the Egyptian intelligence.

The author argues that it is not possible that it was not the Mossad, because it was trying to protect its agent, despite the fact that the golden rule of intelligence officers is to never reveal the identity of your former agents under any circumstances because it would decrease your chances in recruiting other agents of the same caliber in the future.

How can we believe that the Mossad was unaware of the fact that allowing information about Marwan to be leaked over a stretch of ten years jeopardized the safety of its agent and his family? How can the author use such a weak claim that the Mossad tried to protect Marwan to get to the weaker conclusion that it is not possible that the Mossad was involved in murdering him?

The most absurd conclusion left is that the Egyptian intelligence is the only perpetrator of this crime, because of the similarities with the cased of General El-Leithy Nassif, and Soad Hosny who died in the same way. The author claims that the Egyptian intelligence ordered the liquidation of Marwan after a court in Tel Aviv in 2007, three weeks before Marwan’s death, found Eli Zeira guilty of disclosing Marwan’s identity. For him, by liquidating Marwan the whole case would be closed forever because the conviction of Zeira means that Israel publicly admits that Mawaran was an Israeli agent.

But Bar-Joseph overlooks the following facts:

1- The British authorities did not declare that the Nassif and Hosny were murdered in in 1973 and 2001 respectively. The British police said Nassif likely fell to his death because he suddenly felt dizzy, and Hosny likely committed suicide. So how a renowned researcher make such assertions that are not supported by official investigation?

2- A court ruling that Zeira was responsible for disclosing Marwan’s identity cannot be used to conclude that the latter was loyal Israeli agent. The ruling has not addressed this aspect of the case and it is not business of the judiciary to settle a case in which the intelligence is involved. Such cases are considered by special committee away from the jurisdiction of the judiciary.

3- The book ignores the fact the Mossad in 2012, when it was headed by Meir Dagan, closed the investigation into the case of Marwans’ identity disclosure without pressing any charged against Zeira. This means that Bar-Joseph not only ignored this fact but also claimed that Marwan’s case was settled in Israel in 2007.

4- Although the death of three Egyptian known figures in the same way raises suspicions that the Egyptian intelligence might be behind their death, the possibility that other parties wanted to get rid of Marwan cannot be ruled out. The perpetrator might have taken advantage of rumours that the Egyptians were to blame in the two previous cases to kill Marwan in the same way. The aim is to mislead the British authorities and assert that Marwan was a spy and that the Egyptian intelligence service took revenge on him after it was certain of his treason. The Mossad might be this perpetrator.

5- Generally speaking, Bar-Joseph built his case in the other way round using an approach similar to wishful thinking. Due to his relationship with it maybe, he wished to help the in Mossad in restoring its reputation as a legendary intelligence service after it was damaged by suspicions that Marwan was a double agent and its similar fiascos later on. That is why he started with the conclusion he wants, which is that Marwan was a loyal Mossad spy. Then he attempts to close a gap in the old story and uses conflicting information and arbitrary assessments to negate the double-agent hypothesis to present a flawed account of Marwan's murder at the hands of the Egyptian intelligence, which, again, is built on a an evidence base which is neither convincing nor can be adopted a renowned academic.

In conclusion, “The Angel” does not present a coherent hypothesis about Marwan being a Mossad spy, and cannot be taken as an official Israeli account although it cites information not attributed to sources. The sources are maybe the Mossad’s secret archive to which the author had access. Yet, the book is just one of the several accounts presented by researchers and journalists on the same case.

Similar experiences indicate that it is impossible to close such cases forever because researchers and journalists spend long attempting to present more plausible and coherent accounts to the audience using loopholes in earlier accounts. What drivers fresh attempts is perhaps the discovery of gaps in earlier accounts, the emergence of new information that can change the course of investigation. Cautious reading of such books and the information and analyses cited is recommended because they can be used as part of a continuous psychological warfare between warring or rival states.