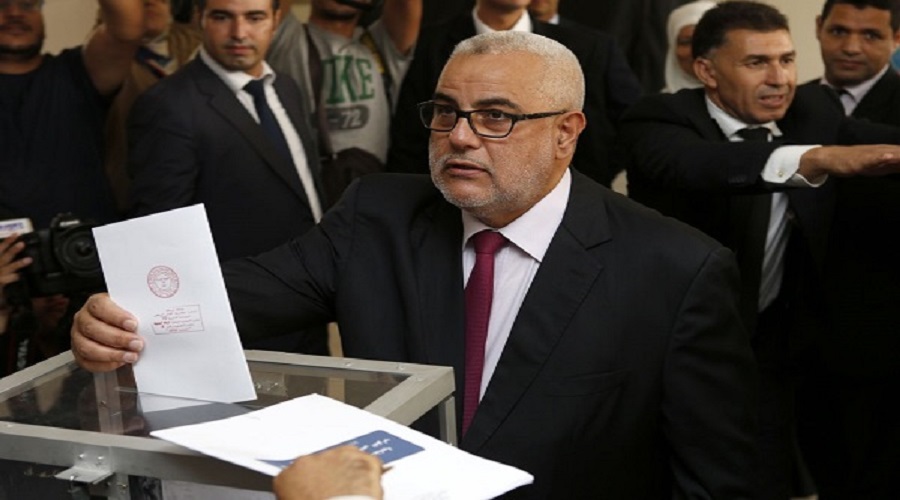

Morocco’s parliamentary elections on October 7 resulted in another victory for the Islamist Justice and Development Party (PJD), despite intense competition from its liberal rival Authenticity and Modernity Party (PAM). The election results, both regarding the distribution of seats and the voting turnout, represent a new political reality with implications for the political party landscape in Morocco, as well as the entire social contract. It is vital to study the reasons for the PJD's victory closely, voters’ behavior during the elections and what can be learned about the political and social realities they reflect.

Seven observations

The 395 seats in Morocco’s lower chamber, the House of Representatives, are divided into 305 local seats and 90 that are voted on the national scale. The October 7 poll results gave 125 seats to the PJD (98 local and 27 national) - 18 more seats than they won in the 2011 elections in which the party also came first. PAM came in second place with 102 seats (81 local and 21 national), gaining more than double its votes in the 2011 poll.

Other parties lost large chunks of their support compared to the last election, with the Independence Party winning just 46 seats, the National Rally of Independents (RNI) winning 37, the Popular Movement taking 27, the Socialist Union 20, the Constitutional Union 19, the Progress and Socialism Party 12 and the remaining seven seats divided among smaller parties. Several primary observations can be made about these results.

1. The number of seats won by the PJD and the PAM came at the expense of the remaining parties in parliament, whose share of the seats fell remarkably. Members of the Democratic Bloc, an alliance of the Socialist Union of Popular Forces (USFP), the Independence Party and the Progress and Socialism Party were particularly hard-hit.

Among the reasons were the two main parties’, the PJD and PAM, high level of organization and continuous communications with the electorate throughout the past five years, through public speeches, parallel groups such as youth parties, and the exploitation of civil society organizations associated with the parties, which offer various kinds of assistance to attract voters to their camp. The PAM and the PJD also adopted skillful media strategies that revealed their effectiveness - particularly that of the PJD, which understood the importance of social media in shaping public opinion and its impacts. This was evident from the way the PJD party supported and financed an electronic brigade among its youth division, to defend its position on important issues related to the party.

2. Both major parties penetrated new electoral districts, enabling them to take new seats on local electoral lists. This was notable in the south of Morocco, which was a stronghold of the Socialist Union, the Independence Party, the RNI and the Popular Movement, and large cities such as Fez, Casablanca, Agadir and Marrakech, where even parties with a long record of political history such as the Socialist Union failed to make headway.

3. Two-party polarization. The PJD and PAM won a combined 227 seats, amounting to 57.5 per cent of the total 395 seats, pushing Moroccan party politics towards an emerging polarization between two major parties. This will likely force the remaining parties to join either one camp or the other, either in government or opposition.

4. The two-way polarization that appears to be emerging is different from the system that dominated Morocco in the 1960’s to the 1990’s. The Moroccan left, in its various factions, used to constitute one pole, which stood in opposition to the parties supported by the institutions of the monarchy amid mutual antagonism. Currently, the PJD and the PAM differ in identity - the former being conservative, with a religious foundation that uses Islamist discourse for political purposes, while the latter is a secular progressive party. Despite those differences, they agree on a fundamental point; both support economic liberalism and free markets.

5. The total collapse of the Federation of the Democratic Left (FGD), a group of three parties that boycotted the elections for years. The FGD, which includes the Socialist Democratic Vanguard Party (PADS), the National Ittihadi Congress Party (CNI) and the Unified Socialist Party (PSU), won only two seats. This reflects the weakness of its communications with the public, which were limited to the use of social media along with occasional TV and radio appearances by its president, Dr. Nabila Mounib. A successful campaign would have required communication with voters throughout the five years as well as visits to cities across Morocco to directly communicate with voters.

The federation’s blurry position on Moroccan politics over the past few years, which has fluctuated between participation and boycott, and its concentration on issues such as parliamentary monarchy, the independence of the judiciary, accountability of officials and fair distribution of wealth, failed to attract votes from the targeted educated classes, as most of which boycotted the bloc. The FGD also neglected to attract voters who found it hard to understand this kind of issues but were won over by the discourse of the PJD, which uses the Moroccan dialect to communicate with voters and adopts religious rhetoric to win over mainstream Moroccan society, which effectively determines who wins and loses elections.

6. Contrary to what many Moroccan observers have said, the PAM is not the biggest winner in these elections but rather the biggest loser - alongside the FGD. The party, which was founded on August 8, 2008 by Fouad Ali El Himma, currently an advisor to the King, gained a lot of attention, won over candidates from other political parties and invested in a media campaign to attack the program of the PJD, in the hope of winning a major victory on October 7.

However, PAM head Ilyas El Omari aggressively attacked the PJD, repeatedly confirming that the PAM opposed the ruling party’s social program, which it labeled as a project to empower the Muslim Brotherhood. That discourse increased the popularity of the PJD and led to its victory in the elections. Many Moroccans did not easily understand the rhetoric used by the PAM due to their education and upbringing. Many perceived it as an attack on Islam, and they decided to vote for the PJD without fully understanding the social programs of the different parties, their ideological framing or their promoted political visions.

Indeed, following the October 7 poll, the PAM is in crisis. Starting off as a political project set up with the primary goal of leading a government as soon as possible, it currently faces a crucial turning point that could define its future, which looks increasingly murky given a lack of patience among its supporters in business and the country’s economic power-brokers. They may give up on the party if its performance does not improve in the 2021 elections, as their economic interests depend on having an extensive network of influence among the ruling parties in parliament. Therefore, the bipolar system that emerged from the October elections may be fragile and short-lived.

7. The level of voter turnout in the elections. Elections are a crucial stage in the democratization process and give a fundamental criterion to measure how voters are responding to the programs of political actors, based on the abilities of the latter to protect citizens’ civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights. The behavior of Moroccan voters depends on several factors.

Economic and social status plays a role; the middle classes tend to participate more when their conditions improve, whereas they protest votes or boycott elections in response to crises. Many voters have little awareness about politics and vote instead of by tribe, clan, aid and monetary incentives, along with, the use of religious discourse for political ends, whereby politics and religion have become intertwined.

According to the Interior Ministry, turnout at the October 7 poll was 43 per cent of the 16 million Moroccans registered to vote - although that figure amounts to only a quarter of the possible electorate. Some 23 million Moroccans over the age of 18 have the right to vote. Such low participation has worrying implications for the future, reflecting the failure of the main political parties to convince Moroccans that voting is of any value. That raises the issue of the future social contract in Morocco, which remains uncertain given that 75 per cent of Moroccans with the right to vote boycotted the elections.

Such boYcotts could lead to growing public anger in the medium term as the PJD continues to implement reforms demanded by the International Monetary Fund - reining in macroeconomic imbalances by implementing austerity measures such as lowering public expenditure, reducing public sector wages, raising the retirement age and removing subsidies from basic commodities, without taking into account the average citizen’s purchasing power. No political system can afford to overlook boycotts, which are an important indicator of divisions within society and can be a warning sign to the political system, which has a duty to improve the political and social situation in the country, raise living standards, develop the economy, raise educational standards and avoid escalating conflicts in society.

Scenarios for the next government

Article 47 of the Moroccan Constitution states that the King has the right to appoint the head of government from the political party that wins elections to the House of Representatives, and to appoint members of the government according to the recommendations proposed by its leader. This gives the PJD the right to begin negotiations with other political parties to form a majority (198 seats or more) and establish the next coalition government.

The next governing coalition formed by the PJD is likely to be along the lines of four possible scenarios:

- A repeat of the previous governing coalition which included the RNI, the Progress and Socialism Party and the Popular Movement Party, which would give it a majority of 201 seats.

- A replica of the coalition the PJD led when it first took office, which included the Independence Party, the Popular Movement Party, and the Progress and Socialism Party, which would give it a majority of 210 seats.

- A coalition with the PAM, giving it a comfortable majority of 227 seats.

- Failure to form a coalition that gives it a majority in Parliament, which would mean that new elections are required.

The first two scenarios are the most likely, given the flexibility the PJD enjoys due to a large number of seats it has won and its likelihood to persuade the other parties to join it in government. The third scenario would be difficult to achieve given the intense rivalry between the PJD and the PAM, while the fourth scenario is even less likely as the Moroccan political system could not cope with its implications and the enormous financial and political costs it would entail. That is especially true given the monarchy’s efforts to present the international community with a positive picture of Morocco’s constitutional and electoral structures.