Amid the current political rise of the far right in European societies, it seems there’s rapprochement between a wide segment of the far right and Russia. One can argue that Russia, in one way or another, aspires to find a new formula for Europe - one that harmonizes with its interests and that doesn't cause Russia any problems in regions that are part of its historical vital areas of influence.

Given this context, questions are raised regarding the motives of the relation between Russia and far-right parties in European countries. European Commission Vice-President Frans Timmermans said, “The reason Putin supports the far right in Europe is that he knows that this weakens us (European countries) and divides us and divides Europe.”

Putin’s Strategy

Since his return to the presidency in 2012, Russian President Vladimir Putin has sought to adopt an expanded strategy to meet Russian interests. This strategy is not only limited to traditional military tools, but it also includes establishing a network of foreign relations with political parties that are ideologically close. Valery Gerasimov, Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Russia, launched a new approach to achieve political and military aims via “indirect and asymmetrical methods.”

Developing this strategy was closely linked to the desire to reach western European countries, which are very different from neighbouring Russian countries and eastern European countries. Moscow’s historical legitimacy and major weight enable it to influence the latter. Establishing political alliances with far-right parties and movements in Europe, in addition to the ideas these groups promote and which are close to Putinism, have paved the way to renew Russia’s foreign legitimacy.

During the past years, Russia formulated three basic models to support the far right inside Europe:

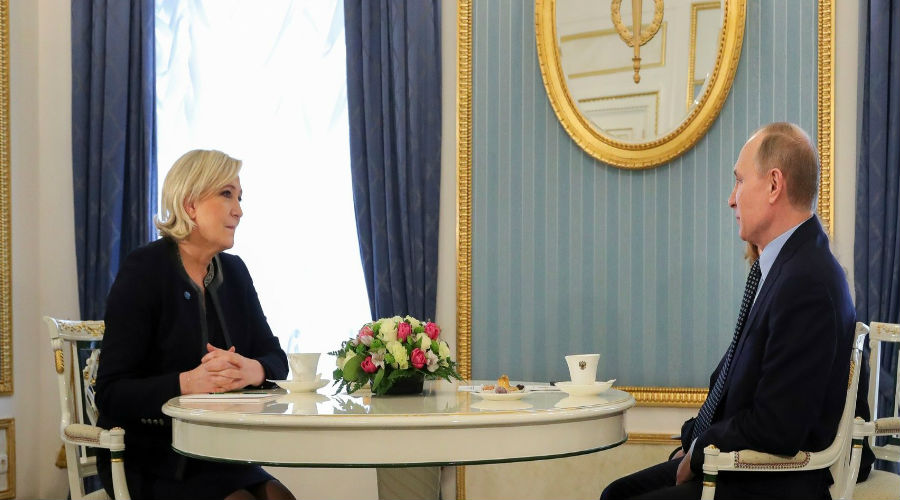

1. Political visits by inviting the symbols and leaders of such movements to visit Russia and coordinate with them. In May 2013, Bruno Gollnisch (one of the symbols of the National Front far-right party in France) visited Russia. Marine Le Pen, the French presidential candidate and the former chief of the National Front, visited Moscow several times, and her last visit was in March 2017 when she met with Russian President Putin in the Kremlin.

In December 2016, the Freedom Party of Austria, a right-wing political party, signed a cooperation agreement with the ruling Russian party, United Russia, to coordinate and ensure a mutual stance on a number of cases. Norbert Hofer, the then-chief of the Freedom Party, said “cooperation with the United Russia Party is tantamount to a gesture towards peaceful cooperation.”

2. Financial support. Despite the difficulty of tracing the tracks of financial funding to far-right parties in Europe, the relation between the French National Front and Moscow revealed the role of the money factor in terms of Russian support to European right-wing parties. In 2014, the National Front received a loan worth 9 million Euros to fund its activities. It received the loan via the Czech Russian Bank headquartered in Moscow. This is according to the website of the Voice of Russia radio network on November 23, 2014. On December 22, 2016, a Reuters report stated that the National Front requested a loan worth 27 million Euros from Russia to fund the party’s participation in the presidential and legislative elections in 2017.

3. Media support for far-right movement members as many of the movement leaders, such as Nigel Farage, the leader of the UK Independence Party, Geert Wilders leader of the Dutch Party of Freedom and Marine Le Pen, leader of the French National Front, were frequently hosted by Russian media outlets.

This media support helped stir trouble for parties that oppose the far-right movement. Perhaps this year’s French presidential election is an example to that as newly-elected President Emmanuel Macron’s campaign team prevented the Russia Today television channel and the Russian Sputnik news agency from entering its headquarters. The campaign’s spokesperson justified this ban by saying that Russia Today and Sputnik have “systematic desire to issue fake news and false information.”

Motives for Support

Alina Polyakova, the director of research for Europe and Eurasia at the Atlantic Council, presumes that enabling far-right parties in Europe helps Russia reformulate the European system in a way that serves Russian interests.

Based on this hypothesis, Russia’s support to the far right, while confirming there are exceptions to this relation, seems to depend on the following motives:

1. Intellectual rapprochement: Many far-right parties share the same narratives which “Vladimir Putin’s Russia” are based on, particularly when it comes to elevating the status of nationalism and conservative social values and to criticizing the EU and American policies. There is also the desire to impose immigration restraints for the purpose of confronting “Islamic radicalism.” This is in addition to doubting the values and basis upon which liberalism was founded. They justify the latter suspicions by citing the economic and social crises which liberalism has led to.

Many far-right parties and movements in Europe view Putin as the model of the strong character they aspire to imitate. Nigel Farage describes Putin as a “great strategist.” Marine Le Pen has on several occasions voiced her admiration for the Russian president, describing him as a model “of reasoned protectionism, and (he) looks after the interests of his country and defends its identity.”

2. Foreign legitimacy: Allying with far-right parties provides Russia with sources to add legitimacy to Russian policies. Moscow used this approach for example during the Crimean status referendum in 2014. The European Union regarded the referendum as illegitimate so Moscow called on a number of right-wing parties like the Italian Northern League, the Belgian Vlaams Belang, the Hungarian Jobbik, the Austrian Freedom Party and the French Front National to monitor the referendum.

Russia also employed its alliance with the far right to support its stances regarding Middle Eastern affairs, mainly in Syria, especially that a wide segment of right-wing parties in Europe agree with the Russian stance, one way or another. The Austrian Freedom Party thinks that Russia is an important factor in settling conflicts in Syria.

The Belgian Vlaams Belang blames the EU for escalating the Syrian conflict through its support for groups that oppose the Syrian regime. The Vlaams Belang thinks that being biased to the Assad regime and to Russian President Putin is the entrance towards settling the conflict.

3. Exiting isolation: After Russia’s intervention in Ukraine in 2014 and the annexation of Crimea following the March 2014 referendum, Europe’s isolation of Russia increased. In March 2014, European countries adopted a mechanism for sanctions against Russia. These sanctions included several measures such as banning visas, freezing assets and imposing commercial and financial restraints.

Moscow responded to this isolation in two ways. The first was by adopting counter measures. Russia began doing so in August 2014 when Russian President Putin issued a decision banning the import of many agricultural products from the EU and the US.

The second was strengthening its alliances with the far right inside Europe as the general tendency within the far right supported Russian measures against Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea. The far right also considered that the Ukrainian crisis was a result “of a hostile attempt by the EU and the US to contain Russia and intervene in its areas of influence.” This is why the far-right’s general political orientation opposes the European sanctions imposed on Russia.

4. Weakening rivals: Russia deals with the EU and NATO as opposing parties that seek to undermine its influence. According to a survey by the Pew Research Centre in June 2015, 60 percent of surveyed Russians have negative points of view towards the EU while 80% have similar points of view towards NATO. One third of Russians attribute the deterioration of the economic situation to Western sanctions imposed on Russia.

In this context, Russia’s support for the far right in Europe, along with the far right’s Euroscepticism and its rhetoric that opposes NATO and American policies, serve Russia’s interests by weakening this Western system. It’s not possible to overlook that this Russian belief has gained major momentum after Britain’s exit from the EU. Brexit spurred right-wing parties in many European countries to call for similar EU membership referendums.

Conclusion

Russia did not create the far right in Europe. The far right originated from new factors that surfaced in European cities in the past few years. These factors are characterized by the increased tendency towards isolation, sensing foreign threats and attempting to get rid of the burdens linked to the EU as an entity, which Marine Le Pen describes as an “anti-democratic monster.”

Moscow employed its alliance with this far-right movement to serve its interests and achieve its vision of an international system – a system that recognizes Russian areas of influence, Russia as a leading partner in managing international affairs, and in which the EU’s and NATO’s statuses and ability to intervene in vital Russian zones recede.

Despite the importance of this alliance with the far right for Russia, this alliance may – in the long run and assuming it succeeds in assuming power in more than one European country – face critical problems. The most prominent one is that Russia’s immersion in supporting far-right parties in Europe can undermine these parties’ image and in this case, they will be viewed as an extension of foreign powers and therefore they do not express national interests.

The collapse of the foundations on which the current European and Western system are built may lead to instability in European societies, especially as a large segment in these societies rejects the orientations of the far right, and this will negatively affect Moscow and its interests.