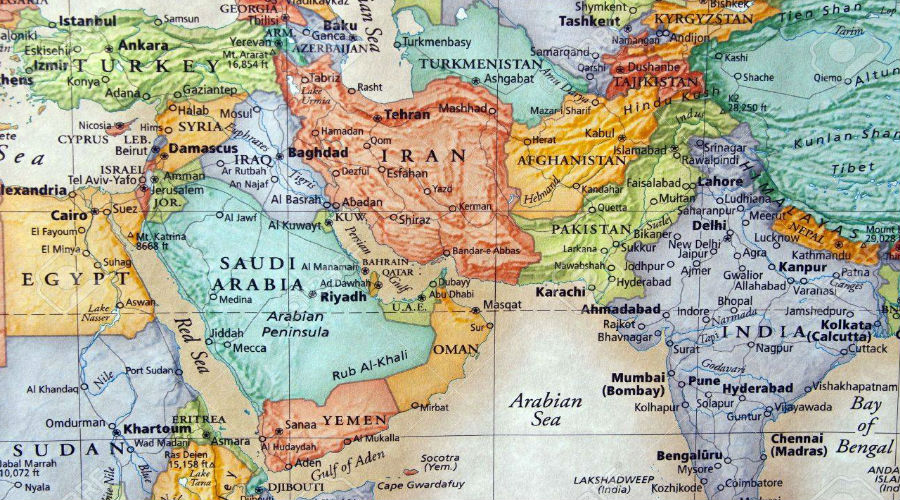

The dynamics of the Middle East region have gained special attention from the three Scandinavian countries (Norway, Sweden and Denmark) over the past years. There are numerous indicators for this rising level of interest. The most prominent of which are the establishment of institutes for dialogue and cooperation, launching programs for the Danish-Arab partnership, opening Middle East studies center in a Swedish university, and hosting a new round of dialogue for the parties to the Yemeni conflict.

Other indicators include providing funds to support future local elections in Libya, supporting non-governmental organizations aimed at assisting internal displaced persons and refugees through local integration or resettlement, and increasing financial incentives for refugees, who return to their home countries. There are various motives behind the Scandinavian interest in the region, including curbing refugee flows, preventing terrorist attacks, containing the threat of extremism, and confronting the Iranian threat.

The Policy of Neutrality

The image of Scandinavia in the literature of international relations is being peaceful democratic states that adopt a policy of neutrality and avoids conflicts in different parts of the world. That is attributed to the fact that those countries do not have colonial history, so they are not preoccupied with rivaling the European Union countries. In addition, they tend to focus instead on internal affairs, which made them top the list of international indicators related to happiness, security and peace. However, the past three decades have seen a change in the areas of interest of these states beyond their national borders and in geographically distant regions, such as those in the Middle East.

The interest of the Scandinavian countries in the Middle East affairs is not new, albeit limited, as it was confined to trade, and investment flows. Another key interest of those countries is participation in the United Nations peacekeeping forces, especially in the light of the UN concern that international forces should be from non-contact states to the parties to international conflicts, which have made them participate in peacekeeping missions in areas such as southern Lebanon and Darfur.

Low-key Diplomacy

An approach of the Scandinavian countries in the region was concerned with the Arab-Israeli conflict, as exemplified by Sweden when it hosted dialogues between the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), Israel and the US, which paved the way for the Madrid Conference at the end of October 1991, leading to Oslo negotiations in 1993. In addition, they launched the so-called “Copenhagen Declaration”, to bring intellectuals, former diplomats and academics from Egypt, Jordan, the Palestinian territories and Israel, together for dialogue - as was the case in the mid-1990s- in the hope of playing a concrete role in the peace process in the Middle East.

It was evident that they had no strategic interests in the region or influence over regional powers. They relied instead they relied on the confidence of various parties acquired through their numerous initiatives and mediation efforts that reflected their awareness of the centrality of the Arab-Israeli conflict to the region’s issues. Such roles have not been met with reservations or objections from Washington. However, the Scandinavian support has changed after the rise of the far-right parties to power.

The Danger of “Others”

The 9/11 attacks have heightened the interest of Scandinavian countries in the Middle East, especially as they host Arab and Islamic communities. This has prompted them to establish institutes for dialogue and cooperation in a number of Arab capitals, key among them is the Swedish Institute in Alexandria (before its closure in September 2018) and the Danish-Egyptian Dialogue Institute in Cairo (DEDI) as part of the dialogue among cultures and civilizations, as well as the Danish-Arab Partnership Program (DAPP).

These institutes and programs aim at reaching out to societies in the region and explore ways to undertake various political, economic, social and cultural reforms, reducing the demographic issues, which is the main driving force of migration flows to Europe.

Active Engagement

The post-revolutionary movement in 2011, which in some cases has devolved into armed conflict in some states, has pushed Scandinavian countries to engage in the region’s interactions, in varying forms, especially in conflict zones, which can be explained as follows:

1. The UN Secretary-General, Antonio Guterres, appointed Norwegian diplomat Geir Pedersen, on October 31, 2018 as UN special envoy to Syria, succeeding Staffan de Mistura. Pedersen had previously held prominent diplomatic posts, including being Norway’s ambassador to China in 2017 and the Permanent Representative of Norway to the UN during 2012-2017.

Pedersen was the UN Special Coordinator for Lebanon (2007-2008) and the Personal Envoy of the Secretary-General for South Lebanon (2005-2007). He also served as Director of the Asia-Pacific Affairs Division of the UN Political Affairs Department. Although this post represents a personal dimension for the Norwegian ambassador, it constitutes a key objective and a common concern of a Scandinavian country seeking to reduce the repercussions of the Syrian crisis.

2. The visit by the Special Envoy of Sweden to Yemen, Peter Semneby, and the official in charge of Gulf affairs at the Swedish Foreign Ministry, Hans Grande Berg, to meet the Yemeni Prime Minister Ma'een Abdulmalik on November 6, 2018. The visit of the Swedish envoy to Aden may be linked to Stockholm’s efforts to arrange for the next round of negotiations between the Yemeni legitimate government and the Houthi militia, a meeting, which it had previously announced its willingness to host.

3. The Danish government contributed 6.54 million Danish kroner to support the future local elections in Libya, which was announced on October 4, 2018, to enhance the capacity of the Libyan Central Committee for municipal elections to raise the awareness of voters and promote the participation of women and persons with disabilities in the electoral process.

Denmark’s stance on the developments of the Libyan conflict was evident in the remarks of the Foreign Minister, Anders Samuelsen. “The long-standing conflict in Libya has caused the country’s security to be extremely fragile. Terrorist groups like IS are still present in Libya. Therefore, we need to step in to stabilize the situation and create a safe environment for the locals,” he said, adding that the country had also become a transit area for migrants on their journey to Europe. “Lasting peace in Libya can only be possible if a political solution is achieved and legitimate and democratic institutions are built up – a process of which local elections in accordance with its people are crucial elements”, Samuelson said.

The implementation of this contribution will be carried out in collaboration with USAID and the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES. The agreement was signed under the auspices of the USAID/Libya Senior Development Advisor Clinton White, and Chargé d’Affaires, Natalie Baker and Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs Special Envoy to the Sahel, Maghreb and Libya, Ambassador Mette Thygesen.

Moreover, the Danish government earmarked 10 million kroner in 2017, to help stabilize conflict-affected areas and to prop up the internationally recognized government of Fayez al-Sarraj, in addition to its contribution to humanitarian efforts and the European Union Emergency Trust Fund for Africa. The Danish interest in the Libyan crisis was evident in the talks between the foreign ministers of Italy and Denmark on November 7 in preparation for the Palermo Conference in southern Italy on November 12 and 13, 2018.

4. The Danish government announced, on May 17, 2018, the withdrawal of one third of its special forces from Iraq (60 soldiers), after the liberation of most of the areas under ISIS control. According to a statement issued by the Ministry of Defence, the gradual withdrawal will end in late autumn. Denmark still has about 180 military personnel at al-Assad airbase in Anbar province, contributing to surveillance and radar maintenance as part of the US-led international coalition against ISIS. Danish Special Forces have joined the Coalition forces since August 2016, to train Iraqi forces and provide intelligence information, along with air support in the Syrian-Iraqi border areas.

It can be argued that the Scandinavian engagement in the region’s conflict zones is driven by specific motives, which can be summarized as follows:

The Threat of Returnees

1. The growing radical tendencies on the Scandinavian soil: Some of their citizens have joined militant groups in conflict countries, particularly in Syria and Iraq. In addition, there is a constant fear of infiltration of terrorist elements among the refugees after gaining combat experience. Such concerns prompted those countries to take security measures, as well as enforcing the necessary laws to confront citizens returning from conflict zones and battlefields. In this context, the Norwegian security services are enforcing the Anti-Terrorism law No. 147, which provides six years imprisonment for anyone who establishes, forms, participates or recruits members, or provides financial or logistical support to a terrorist organization carrying out illegal acts.

Cross-border Terrorism

2. Confronting dangerous terrorist organizations: Terrorism is one of the mounting threats to the security of Scandinavian countries, which explains the reasons behind Denmark’s participation in the international coalition against ISIS. It should be noted that on January 26, 2017, Danish Prime Minister, Lars Lokke Rasmussen, announced that his country would dispatch a frigate, Peter Willemoes, to the Mediterranean Sea to join the international coalition operations against ISIS. “We are achieving victory over one of the most cruel and brutal terrorist organizations in the world history”, Rasmussen said. The Danish frigate escorted the USS George H.W. Bush aircraft carrier to the Mediterranean and Arabian Gulf during the period between February and May 2017.

Peace-building Efforts

3. Political settlement of armed conflicts: The moves made by Scandinavian countries aim at paving the way for transition from conflict to peace, addressing the causes of threats, foremost among them irregular migration, refugee flows and cross-border terrorism. Although some countries, such Denmark, consider Bashar al-Assad a war criminal, they believe that insisting on his removal from power before reaching a settlement will prolong the conflict in Syria, which is not in the interest of the parties calling for stability and reconstruction.

The Iranian Threats

4. Countering the Iranian threats: On October 30, the Danish government said it foiled an assassination plot by Iranian intelligence to target Ahvaz opponents on its soil, most notably Habib Jaber, the head of the Arab Struggle Movement for the Liberation of Ahvaz (ASMLA). In this regard, the Danish government is rallying the support of its European partners to impose sanctions on Tehran. Although Copenhagen continues to defend the Iranian nuclear deal, it does not condone other issues such as the Iranian ballistic program and interference in regional conflicts.

In short, security risks and threats facing the Middle East countries are spilling over into the Scandinavian countries. Despite being geographically far from the region, the “moving geography” brings the Middle East to countries that are neither alarmed nor engaged with the developments.