Four million Lebanese voters were called to cast their vote in the parliamentary elections held on May 15 to choose 128 representatives. There were 718 candidates in 103 lists from 15 constituencies, an increase of 26 lists from 2018. On the day before the election, the pivotal question was whether these elections will be fruitful, and whether their outcome can be a game-changer in the country’s politics amid fears that the same political dynamics would be just replicated once again?

The most hopeful expectations are yet that change will be limited if it ever happens. The results of the elections were, however, as surprising as a “tsunami”, as the 17 October Revolution forces came with force to sweep Lebanon’s political landscape.

Major Indicators

The following factors contributed to the outcome of Lebanon’s parliamentary elections.

1. A lower rate of participation:

The rate of participation in the recent general elections stood at 41 percent, down by 8 points compared to 2018. The highest rate was recorded in the Christian constituencies, specially Jubail-Keseran and the third North constituency. The rate was notably high in the Chouf-Aley constituency, while Shiite-majority constituencies were less enthusiastic to participate in the vote where only 40 percent of voters cast their ballot although Hezbollah mobilized its leading figures. Ahead of the election, chief of Hezbollah, Hassan Nasrallah, said ink stained fingers help keep his finger pointed high after the elections. Sunni-majority areas recorded the lowest rate of participation with 30 percent. This rate could have been even lower had it not been for expatriate Lebanese excited about the elections one week ahead of the voting day who encouraged many citizens at home and gave them hope that change is not impossible. This was especially so because a majority of expatriate voters stood for the forces of change.

2. Gains of the Forces of Change and Hezbollah’s loss:

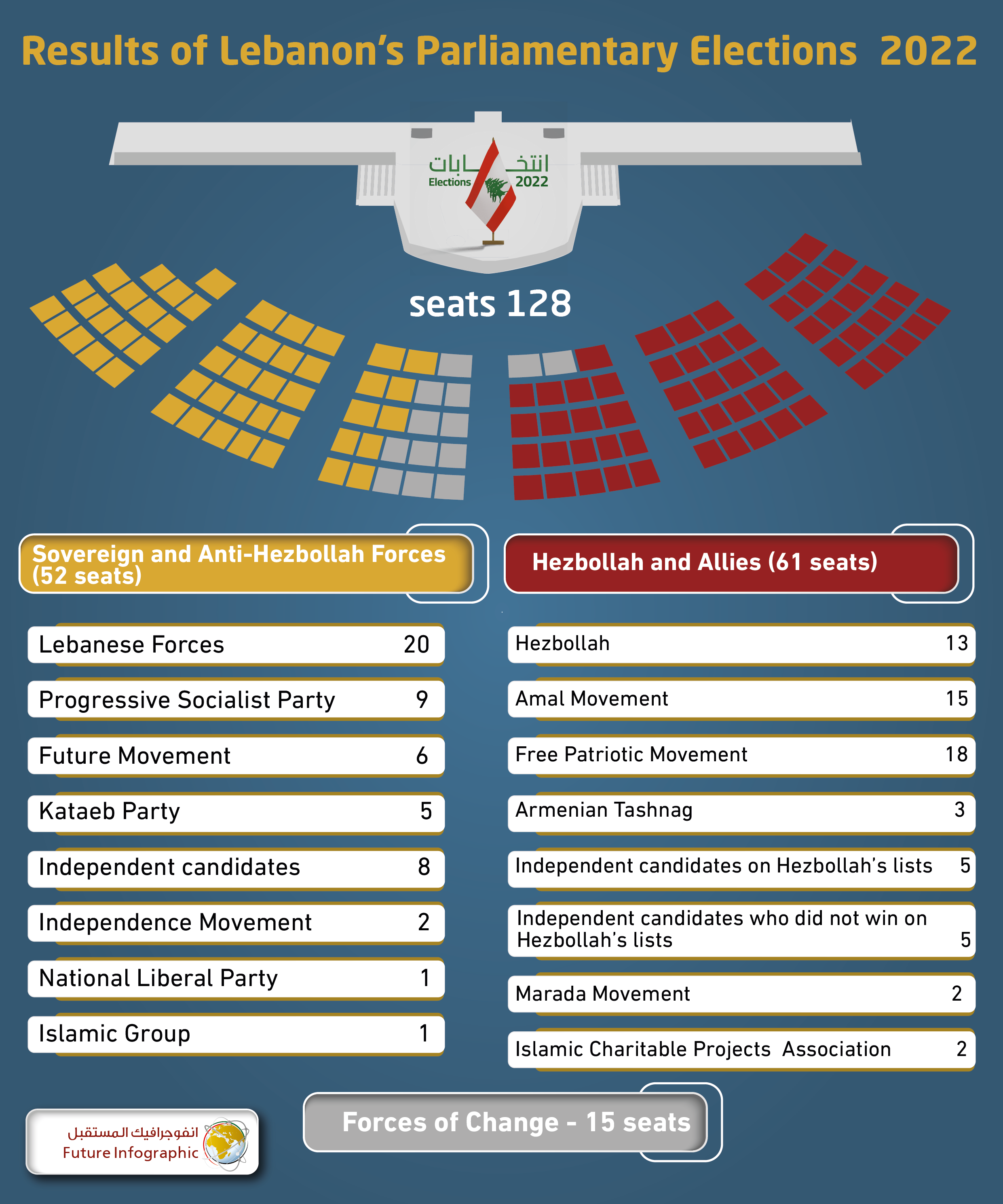

The results of the 2022 elections showed that the biggest winners were the Forces of Change which surprisingly and unexpectedly managed to win 15 seats. Moreover, by winning 20 seats, the Lebanese Forces was able to impose itself as the most powerful Christian party. The biggest loser was Hezbollah whose chief insisted that this year’s elections were “the battle of allies”, and worked hard to coordinate between his allies to divide quotas. Nasrallah sought to convince the Free Patriotic Movement and Amal Movement to run on the same lists, held a meeting, at his headquarters, with both Gebran Bassil and Sleiman Frangieh, and withdrew some of Hezbollah candidates in order to support allies. He withdrew Albert Mansour, who was running for the third Bekka constituency to support a candidate from the Free Patriotic Movement. But despite all its attempts, Hezbollah lost its allies’ seats, including that of Elie Ferzli, Assad Hardan, Wiam Wahhab as well as two seats in the Jezzine and Koura constituency.

3. Different power-distribution in the parliament:

The undisputed fact in the new parliament is that Hezbollah and allies lost their parliamentary majority with its share going down from 71 seats (2018) to 61 in the most recent elections. But there are different views on how to categorize the remaining 67 representatives. Some have it that the new parliament features a bi-polar mix of 61 pro-Hezbollah representatives and 67 anti-Hezbollah representatives. Others believe that it is a tri-polar parliament where the first bloc is Hezbollah and allies (61 representatives), while the second consists of so-called “Sovereign Forces” i.e. the Lebanese Forces, the Progressive Socialist Party and other figures (52 representatives), and the third consists of the forces of change (15 representatives). But it is likely that the Sovereign Forces and the Forces of Change will agree on the need for disarming Hezbollah. Regarding other issues, including how to run the country and revive its economy, a case-by-case majority is likely to form and take shape depending on the issue on the table.

Implications of the Outcome of the Elections

The following are outstanding implications of Lebanon’s 2022 parliamentary elections.

1. The 17 October Revolution imposing role:

External and internal interactions in the wake of the August 4, 2020 Beirut port explosion failed to force the authorities to hold early elections. Then, the call for early elections was rejected by Hezbollah at a meeting held in August 2020 at the Residence des Pins and attended by French President Emanuel Macron. Then, there were fears raised by a wave of change that was at its peak. Some parties in power turned down the call believing that with time, the government will restore control of the streets and the supporters of the 17 October Revolution will lose hope. As the May 15 elections were approaching, there were views that it is hard for the elections to bring about a change as the Lebanese grew less enthusiastic about change. But the outcome of the elections showed that the Forces of Change won 15 seats and are not unlikely to align in one powerful bloc, set to become the largest in the parliament.

2. Hezbollah maintains influence in affiliated areas:

Hezbollah succeeded in silencing the Shia population which aligned with the 17 October uprising, either by accusing foreign powers of influencing this revolution, or by using violence, including burning down tents set up by 17 October Revolution members in the militia’s strongholds. Despite that, the participation rate of the Shia population in the recent elections went down 10 percent to 40 percent, compared to the 2018 elections. This shows that some Shiite opted for boycotting the elections rather than voting against Hezbollah and its allies. But eventually, Hezbollah and the Amal Movement managed to win all the Shia seats in the parliament.

3. Hezbollah lost Christian cover:

The results of the elections revealed that pluralism was restored to Christian forces where Hezbollah’s allies are no longer a majority. The Free Patriotic Movement won only 18 seats, down from the 29 it won in the 2018 elections. Moreover, the Lebanese Forces, an opponent of Hezbollah, won 20 seats, while the Kataeb, another anti-Hezbollah party, won 5 seats. It was expected that even if the Free Patriotic Movement’s Christian popular base eroded, the Lebanese Forces and Kataeb, combined, would not win a larger share of seats. The expectation was wrong and the results revealed that a majority of Christians backed forces that are Hezbollah’s Christian foes.

4. Sunnis did not note for a replacement to Saad Hariri:

After the elections, it turned out that the Sunnis are still shocked by Saad Hariri’s withdrawal from politics. As a large segment of Sunnis abstained from voting, the rate of participants in the Sunni constituencies went down to 30 percent. The largest declines in Sunni votes, compared to the 2018 elections, was recorded in Sidon (16% decline), Mineyeh (15 percent), Danniyeh (15 percent) and Tripolic (10 percent). A segment of Sunnis voted for the Forces of Change, which enabled 6 out of 15 candidates from these forces to win the elections. These are Ibrahim Mneimneh from the second Beirut constituency, Rami Fanj and Ihab Matar from the second North constituency, Yasine Yasine from the second Bekaa constituency, and Halima al-Kakour from the Chouf-Aley constituency.

The main goal of Sunnis remains to oppose Hezbollah’s plans in different ways. This was evidenced by a substantial decline in votes given to Sunni candidates allied with the 8 March Alliance or with Hezbollah, such as Hassan Murad, Jihad al-Samad and Faisal Karami. That is, evidently, Hezbollah failed to take advantage of Saad Hariri’s withdrawal to win Sunni votes. Moreover, candidates backed by the two former prime ministers Najib Mikati and Fouad Siniora, failed to win seats at the parliament. The only seat won by the “Beirut Confronts”, backed by Siniora, went to Faisal al-Sayegh, who is an ally of Druz leader Walid Jumblat. Additionally, the only seat won by the “Al-Nas” list, backed by Mikati, in the North Lebanon constituency, went to Abdul Karim Kabbar, son of former minister Mohammed Kabbara.

5. Druz gathering around Jumblat:

The fall of Talal Arsalan, the second most influential Druz leader, was remarkable and is set to help Walid Jumblat’s endeavors to become the sole leader of Druz (through winning 7 out of 8 seats for Druz), despite Hezbollah’s attempts to besiege Jumblat by backing his opponents and even having them on its lists. These include, alongside Arsalan, Wiam Wahhab and Marwan Khairiddin, who all emerged losers, a significant sign that Hezbollah’s popular base and its so-called armed resistance plans, within other sects, has already eroded.

Multiple Hindrances

The results of the recent elections are likely to impose challenges on the political landscape. These can be outlines as follows:

1. Choosing a new parliament speaker:

The term of the new parliament already started on May 22. The problem of electing a new speaker is that even if Hezbollah and Amal Movement managed to keep Nabih Berri for a seventh term at the helm of the parliament, other large Christian blocs, including the Lebanese Forces and the Free Patriotic Movement and even the Kataeb, will not be interested in voting for Berri because of a deep political rift. This can represent a conundrum, because, according to the country’s constitution, the legitimacy of the authorities is derived from their honoring of the principle of coexistence. Moreover, Hezbollah’s loss of the majority (61 seats) can, theoretically, add yet another dilemma: how can a speaker opposing Hezbollah and is opposed by a majority of the Shia MPs, be elected when Hezbollah is in control of the Shia seats?

That is why a possible scenario goes like this: those MPs who oppose Berri

would vote through a “white paper” for a new term for him, while the number of Sunni and Christian votes for him would significantly decline.

2. Forming a new government:

The term of the current government headed by Mikari is practically over after the new parliament starts its term. As a new government is to be formed, the most possible scenario is that the president, Michel Aoun, refuses to sign a decree mandating the formation of a new government that reflects the new balance of power produced by the elections. This is especially so because his rivals from the Lebanese Forces are now the largest bloc in the parliament. Therefore, it is likely that a new head of government is named but no new government would be formed. As such, the Mikati government will become a caretaker government until Aoun’s term comes to an end in October 2022, or until the new majority agrees to the formation of a new government that is very similar to the current one while the Free Patriotic Movement maintains the same powers in the current government.

3. Electing the next president:

As a result of the recent elections, Samir Geagea, chief of the Lebanese Forces, became the most likely candidate for the next presidential elections after he became the legitimate representative of Christians and won the largest Christian bloc in the parliament, while his rivals Gibran Basil and Sleiman Frangieh, allied with Hezbollah, lost the lead. That is why, holding the next presidential elections in time in October 2022 is unlikely, especially after the 8 March Alliance, in 48 parliamentary sessions, blocked the presidential elections after the term of former president Michel Sleiman came to an end, although this alliance did not at that time hold a majority of seats. The alliance did so by not attending the sessions and taking advantage of being a “blocking third” and therefore a lack of quorum. This makes it likely that electing a new president will be a highly complicated issue and that Lebanon might well suffer from a new presidential void, especially as the current balance of power is in favor of Geagea, a bitter enemy of Hezbollah.

4. Addressing economic deterioration:

Days before the elections, the government eased power rationing and disbursed financial aid to government employees, while keeping the Lira exchange rate below 30,000 to the US dollar. The new measures were aimed at holding the elections with a minimum popular resentment. But the measures put in place to preempt resentment might not last for a long time and can even be removed shortly after the elections are over. The removal of these measures is expected to be associated with a cancellation of fuel, bread, wheat, medicine and even telecom subsidies, a move that will trigger wide resentment among citizens who will question the benefit of participating in the electoral process. That is, the results of the elections are not likely to curb deterioration of the economy and living conditions. Some assessments, however, have it that the reelection of French President Emanuel Macron, and the victory of the anti-Hezbollah majority, will mean that the international community will not ignore Lebanon’s issues, if the new majority is committed to implementing the required reforms.

The overall conclusion would be that the results of the recent parliamentary elections were shocking as the long-standing majority was removed. But beneath this shock lies a substantial challenge that is not new. This is not the first time that an anti-Hezbollah majority wins the elections. The 14 March Alliance did it twice in 2005 and 2009. Therefore, the question begs itself: How can this new majority be governed? Will it be able to push for state-building and combat plans to build a “statelet-within-the-state”?